Mitigating MEV using trusted hardware#

An important problem faced by many cryptocurrencies today is called Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). Transactions are submitted in the clear, and they are prone to front-running and back-running attacks. Such attacks allow the arbitrager to make unfair profit, at the expense of the users who are forced to buy and sell at a less favorable price. Because of such MEV attacks, an offchain ecosystem has developed: block builders now sell favorable positions in the block to both arbitragers and users alike, leading to a centralization effect. Today, 80%-90% of the Ethereum blocks are produced by the largest two block builders [Yang et al.].

To mitigate MEV, the community has dedicated significant efforts to building new private order flow architectures, where transactions are submitted in encrypted format, and blocks are assembled without revealing the transactions.

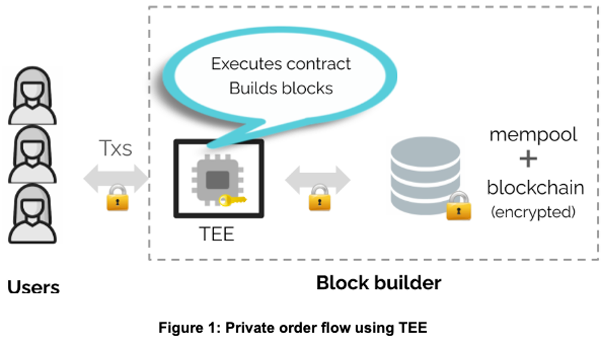

One promising approach to enable private order flow is to use Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). At a high level, the TEEs establish a sandbox (often called enclave) whose security is enforced through tamper-proof hardware. Data in transit or at rest is always encrypted, and only inside the enclave can they be decrypted and computed on. In the case of private order flow, the block builder’s machines (also called the server) are equipped with TEE. The users are submitting encrypted transactions to the server’s enclave, and the server also maintains an encrypted mempool and an encrypted copy of blockchain data. The block building takes place inside the enclave, where the transactions are speculatively executed.

For example, Flashbot’s BuilderNet architecture provides a platform for decentralizing block building. BuilderNet supports TEE to allow secure/verifiable transaction execution, also enabling the option of private block building.

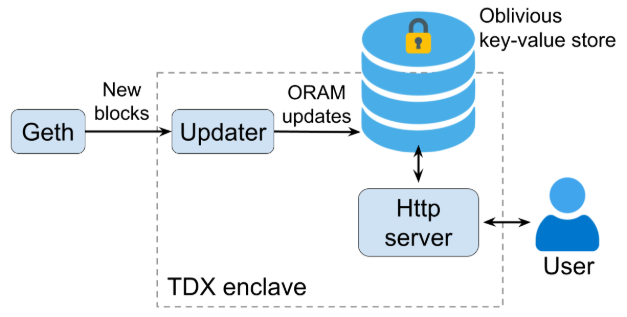

Figure 1: Private order flow using TEE

Understanding access pattern leakage#

Encryption alone is not enough for achieving privacy. As mentioned, to privately build a new block, the block builder speculatively executes the transactions inside the enclave. The smart contract execution requires accesses to the blockchain’s state, and the access patterns are observable by the server.

What is leaked through access patterns?

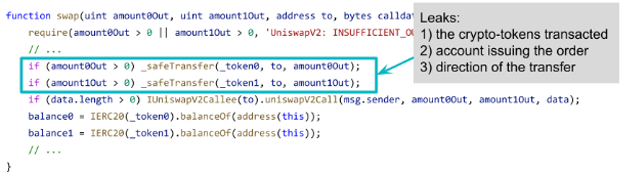

In popular Ethereum applications, these accesses leak highly sensitive information. For example, below we show the core part of a Uniswap contract. The highlighted lines leak sensitive information such as 1) the tokens being traded; 2) the account issuing the order; and 3) the direction of the transfer. This is precisely the information we wish to protect, and encryption alone does little to protect it.

How can the server learn the access patterns?

There are several ways the untrusted server can observe access patterns.

First, if the blockchain’s state does not fit into the enclave’s protected memory, then the enclave needs the operating system’s (or hypervisor’s) help to fetch memory pages from outside the enclave. Here, the page swap can be fetching data from the insecure RAM or from disk. In either case, the OS/hypervisor directly observes the page-level access patterns without having to launch any complex attack.

Even if the blockchain’s state can fit within the enclave’s protected memory, the server can nonetheless observe memory accesses within the enclave through several types of attacks:

- Controlled-channel attacks. The OS (or hypervisor) can unmap certain memory pages of the enclave. Whenever the enclave accesses these pages, a page fault is triggered and served by the OS (or hypervisor). In this case, page-level access patterns are leaked. Pradyumna Shome’s excellent blog post has a detailed explanation of how this attack works on both SGX and TDX. While this post proposes a solution (TD Exit Notify), this will require a change from Intel and thus isn't applicable yet.

- Cache timing attacks. The untrusted OS (or hypervisor) or a co-resident VM can pollute the cache-lines shared with the enclave, and use timing measurements to determine whether a location has been accessed. Cache-timing attacks can allow the untrusted OS/hypervisor to learn fine-grained access patterns, at the cache-line granularity (typically 64 bytes).

- Network access patterns. In the longer term, when the blockchain’s state grows too large, we may want to build a distributed storage layer. In this case, the network routing also leaks information about the access patterns. The granularity of the leakage here depends on the size of the atomic unit requested.

We also stress that simply permuting the data in untrusted storage does not work. It is fairly easy for the adversary to infer which location is storing what through statistical inference, by leveraging frequency and co-occurrence. This is similar to why deterministic encryption is not secure.

Taming the access pattern leakage through Oblivious RAM#

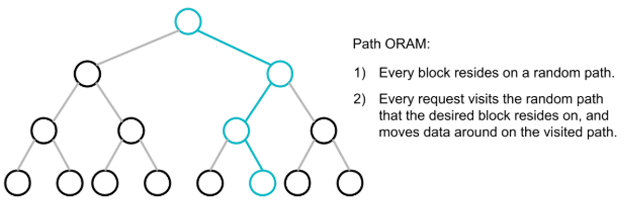

So what can we do to prevent the access pattern leakage? We can use the help of Oblivious RAM (ORAM). ORAM is an algorithmic technique that provably hides a program’s access patterns to data. Below we will give a quick crash course on the Path ORAM algorithm.

Main data structure. First, the main data structure is a binary tree. Every node in the tree is called a bucket. The root bucket has super-logarithmic capacity, whereas every other bucket has capacity 4. Each bucket stores a combination of real blocks and filler blocks. The real blocks are encryptions of actual data, whereas filler blocks are encryptions of 0. The filler blocks are needed for security.

Path invariant. The path invariant says that at any point in time, a block is assigned to a random path, i.e., a path from the root to a random leaf node. Each block must reside somewhere on the path it belongs to.

Operations. To fetch a block, we just need to visit the path the block resides on. The key insight is that we need to relocate a block to a new random path immediately after we read it. Moreover, we cannot disclose the choice of the new path. One way to achieve this is to write the block back into the root bucket. However, as we continue making more requests, the root bucket will soon fill up.

Therefore, we introduce the following eviction process along with every data request: for the path we have just visited, we will repack the blocks on that path as close to the leaf as possible, without breaking the path invariant. We can prove that with this eviction process, no overflow will happen except with negligible probability.

Recursive position map. The last remaining question is, how can we find out which path a block resides on? This is achieved through recursion. Imagine we have a position map that records the path for every block. This position map is smaller than the original dataset as long as the block size is sufficiently large. We now recuse and store this position map in a smaller ORAM tree, until the position map (of the position map of the position map…) is of constant size. In practice, the block size (i.e., the page size) is typically 4KB, and the recursion depth is at most 3 for an Ethereum-sized dataset.

In summary, in Path ORAM, ignoring the recursion, then each request involves visiting only a single tree path.

Performance of ORAM#

Now, you should see that ORAM is just a simple tree-based data structure, and contrary to what many believe, there is no cryptography involved! For this reason, ORAM’s performance is comparable to storing data in a database, i.e., we can enjoy almost native performance. Indeed, the scalability of ORAM has already been attested to in Web2 applications. Notably, Signal, the private messenger, employs ORAM for their private contact discovery service --- see Signal’s blog post on this topic. Prior to adopting ORAM, they relied on a naive batched linear scan algorithm to achieve privacy, requiring ~500 servers. After rolling out ORAM, they were able to cut down to only 6 servers, saving almost 100x in computing cost.

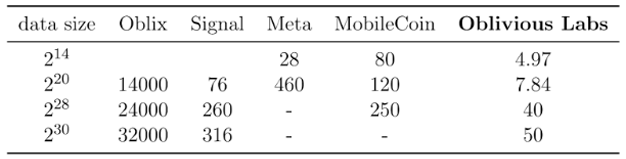

Microbenchmarks. As shown in the following table, our implementation outperforms those of Signal and Meta by an order of magnitude or more. Specifically, at a database size of 2^30, our oblivious key-value store implementation has 50μs latency. Using a batch size of 4096, our throughput is 200K requests/second (at data size 2^28).

Performance of our oblivious key-value store: the numbers are in microseconds (μs)

If you are convinced and you want to use ORAM, you can check out the open-source implementation (MIT license) provided by Oblivious Labs Inc..

Projected performance in blockchain applications. If we want to use ORAM during block building to secure the accesses of all Uniswap transactions, how much delay are we looking at? We looked at the recent Ethereum block data. On average, each block has ~20 Uniswap transactions. Each Uniswap transaction makes 3 memory accesses (sload/sstore operations) that are sensitive. Using our microbenchmarks above, the projected delay for building a block would be 3ms, if we store the entire Ethereum state in ORAM. The latency can be further reduced to 0.5ms if we store each uniswap contract in a separate ORAM, but this would leak which pair of tokens are being exchanged.

Demo: oblivious balance checker#

At Oblivious Labs Inc., we have created a demo for an oblivious Ethereum ERC20 token balance checker, allowing a user to check its ERC20 token balance without identifying the queried account. Our demo is available at https://obliviouslabs.com/WBTCdemo/.

Our balance checker demo (shown above) is for the WBTC token. We maintain a fresh copy of the WBTC’s contract state in an oblivious key-value store. We also implemented an updater that keeps reading the newly minted blocks from a geth node. The updater then verifies the Merkle Patricia Tree (MPT) proofs before adding the state updates to the oblivious key-value store. With the oblivious key-value store, a user can query its balances without identifying herself.

Towards an Oblivious Data Access Layer for Ethereum#

Our current oblivious balance checker only provides oblivious accesses for the state of a single contract, but our next step is to extend it and support oblivious queries to the entire Ethereum state as well as blockchain data, based on the same architecture. The end result will be an oblivious data access layer for Ethereum, supporting fast support queries to Ethereum’s full state and logs while hiding the user’s intentions.

Please contact [email protected] if you are interested in collaborating with us.