Today, we introduce a new thesis: MEV has become the dominant limit to scaling blockchains.

At a time when leading networks like Ethereum, its L2s, and Solana are racing to scale as fast as possible, the economic limits imposed by MEV are becoming apparent across the industry. Spectacularly wasteful onchain searching is starting to consume most of the capacity of most high throughput blockchains.

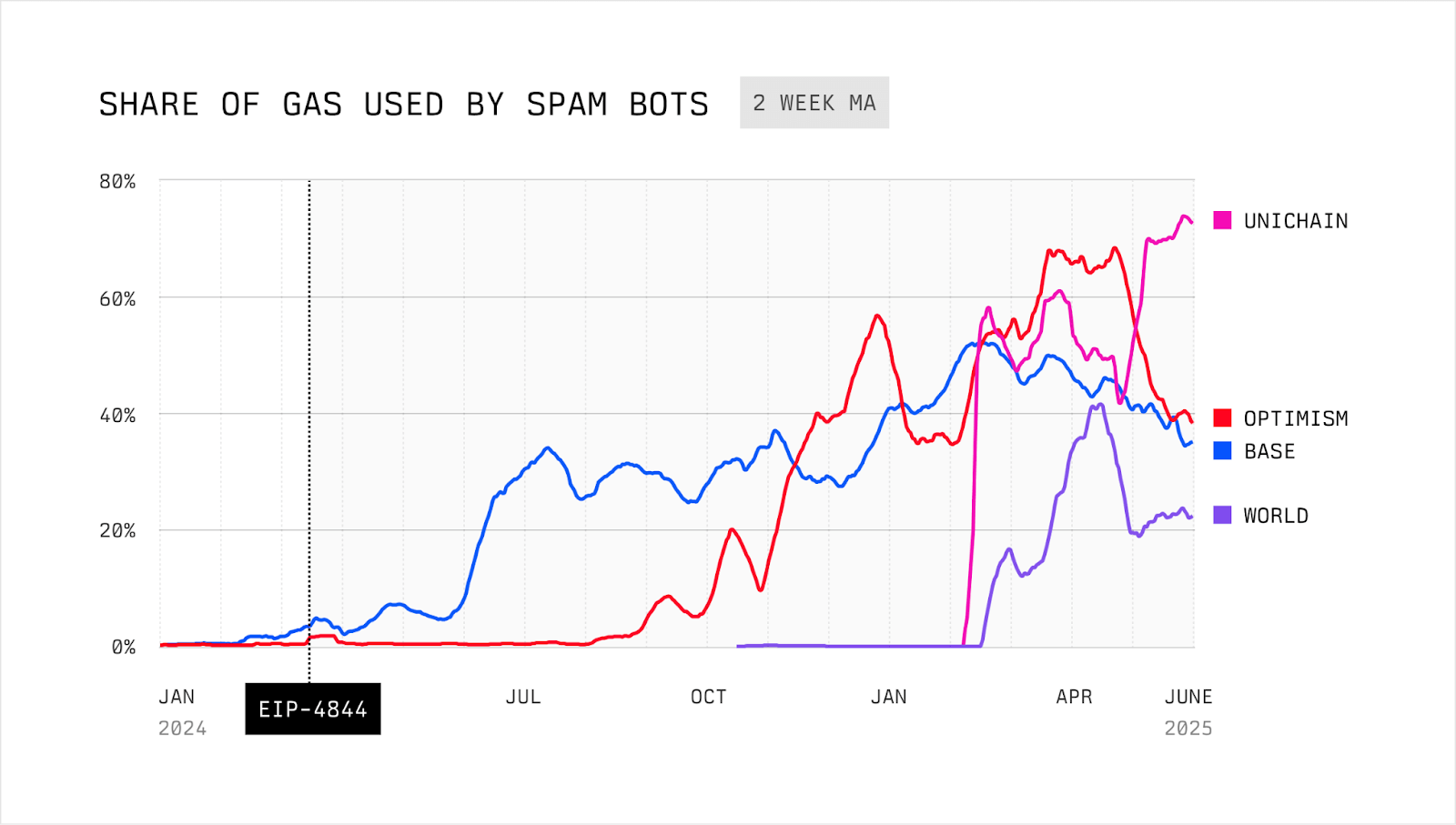

This is not a theoretical or isolated problem. We can observe it everywhere from Solana, where MEV bots consume 40% of blockspace, to the Ethereum L2 ecosystem. To quantify the impact, we conducted a deep dive on top OP-Stack rollups where specific trace endpoints were available. The results serve as a clear window into a market-wide problem:

- Spam bots across multiple rollups are consuming more than 50% of gas and paying less than 10% of fees.

- Between November 2024 to February 2025 Base added 11M in gas/s throughput and almost all of it was consumed by spam bots. (Three Ethereum Mainnets worth of capacity!)

- Spam bots’ constant demand for gas creates persistently higher fees for users.

- The market for spam is extremely concentrated with two searchers responsible for more than 80% of spam on Base.

Technical scaling efforts like database sharding (i.e. rollups), validity providing, or database or consensus optimizations are incredibly important, but ineffective on their own. We know how to build raw technical throughput but the current market structure imposes economic limits on scaling.

In this article, we will unpack this market failure, show data demonstrating its impact, and argue for a new MEV auction designed to solve it.

Anatomy of a spam transaction#

To understand why blockspace is being wasted, let’s first dissect a single, successful arbitrage transaction:

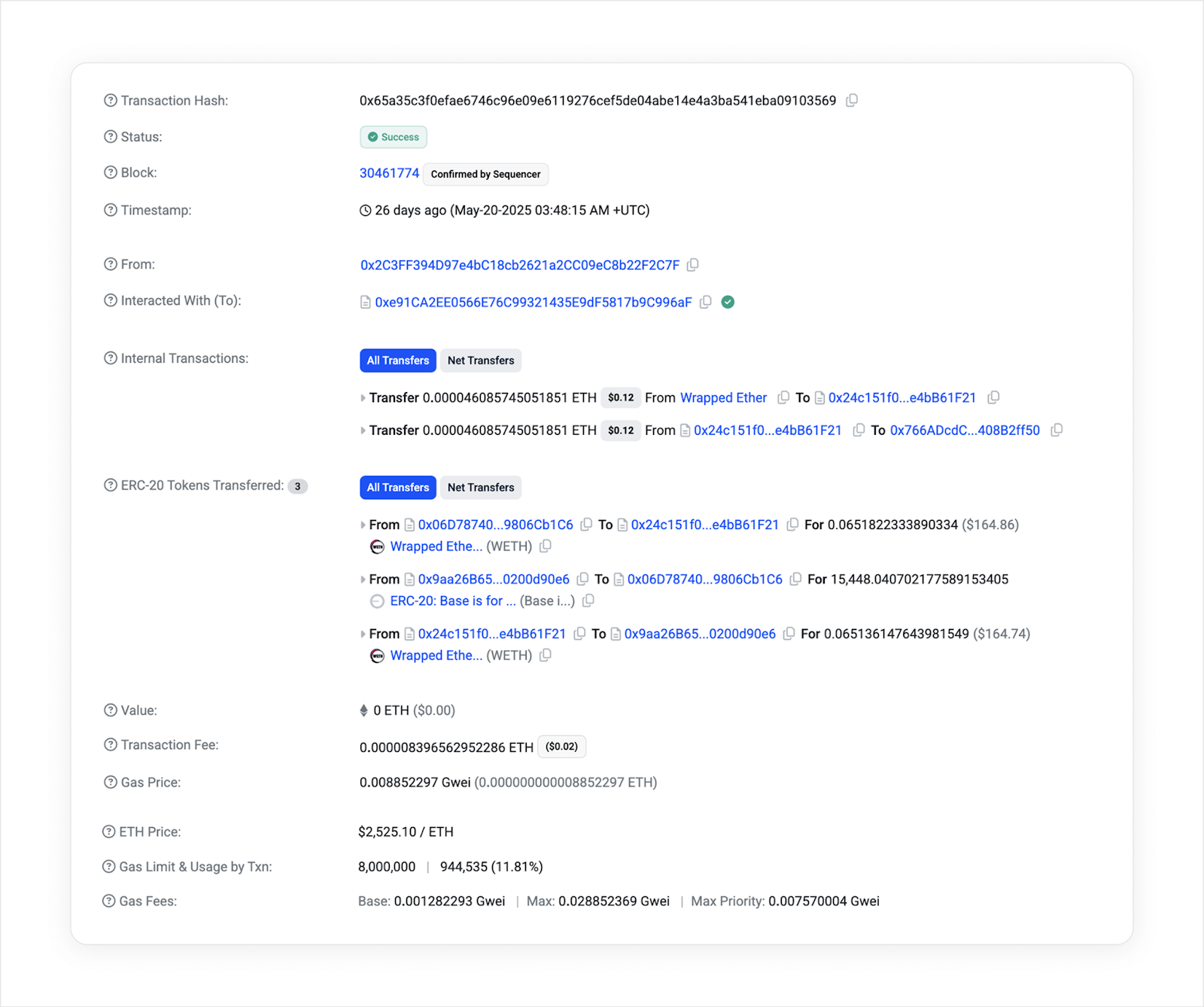

An example of a successful arbitrage transaction on Base.

At first glance, you might think this is the picture of efficiency: a searcher bot executed a precise arbitrage yielding $0.12 and paying $0.02 in fees.

But the true cost of this one successful arbitrage is shocking: For every single successful arb, this bot sends ~350 transactions that try but fail to find an arb. On average, this bot consumes approximately 132 million gas per single successful arbitrage - equivalent to nearly 4 full Ethereum blocks. And keep in mind, this was one among several that was competing for this opportunity, so the true cost to the chain is even higher still.

Now let’s turn to one of the many, many failed attempts to better understand the bot’s onchain activity.

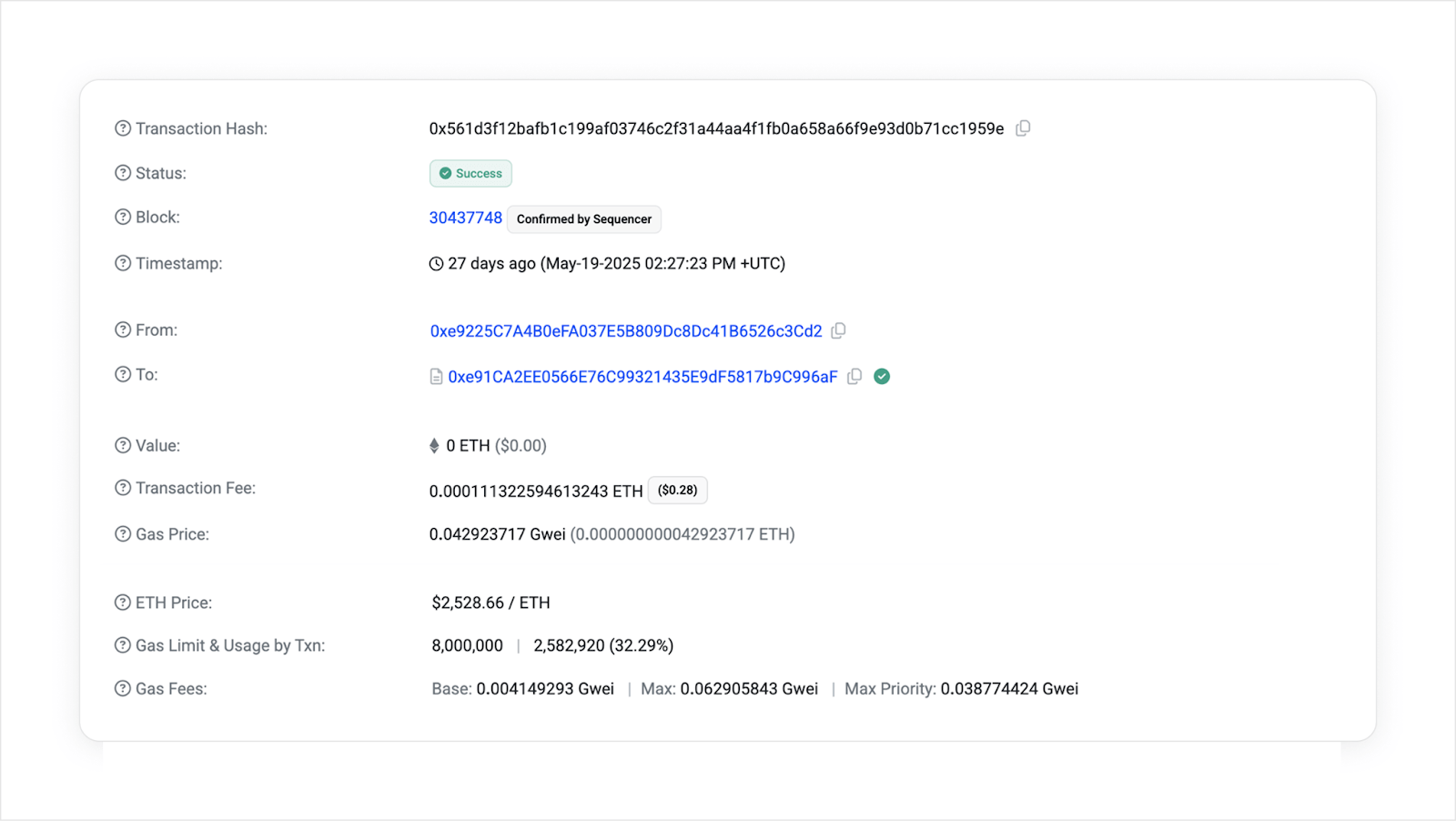

An example transaction that is unsuccessful in blindly finding arbitrage

At a glance this transaction looks innocuous. It executed successfully and performed no token transfers. The only hint it gives us of its true activities is that it uses ~2.6m gas, as highlighted above.

However, if you look under the hood at its traces we can see a long list of calls to dozens of different DEX pools, querying their state with getReserves() and slot0() calls. These calls are essentially getting the prices of different assets on different DEXes.

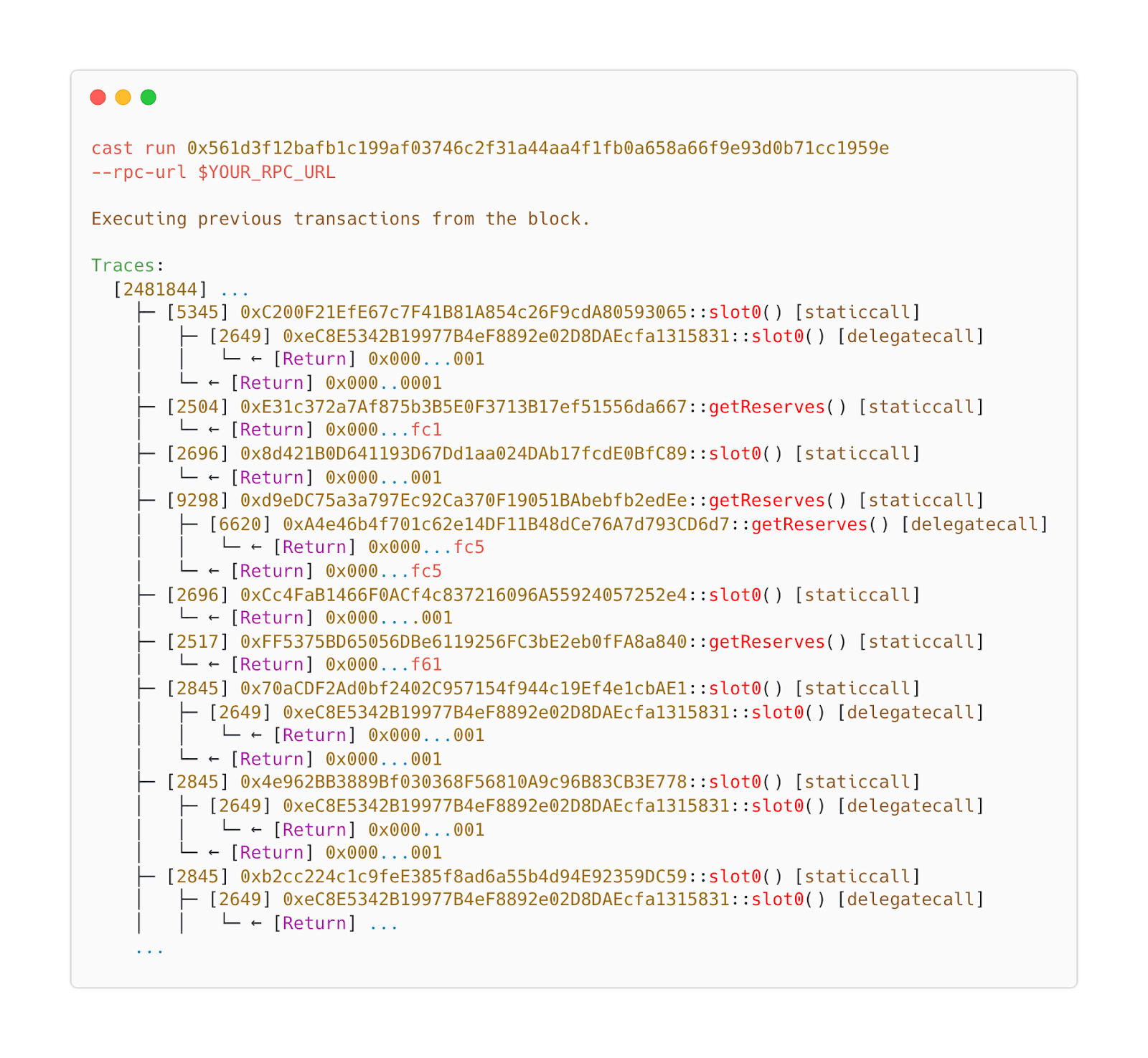

Example traces showing repeated calls of slot0() and getReserves()

cast run 0x561d3f12bafb1c199af03746c2f31a44aa4f1fb0a658a66f9e93d0b71cc1959e --rpc-url $YOUR_RPC_URL

At its core, this bot’s logic is simple:

- Launch a transaction onto the chain.

- Once executing, query the prices of a bunch of DEX pools.

- If a profitable arbitrage exists, execute it.

- If not, do nothing and terminate.

This transaction is these 4 steps in action, ultimately terminating and not doing anything. In effect, it is an intensive price query that consumes ~2,600,000 gas just to read the state of the market and not do anything.

Across chains like Base, World, and Solana this is the dominant strategy for extracting MEV. Many, many failed attempts to find arbs are paid for by just a few successes. Although this is rational for this searcher, it is profoundly systematically inefficient for the network.

Huge amounts of resources are being used just to read prices and not do anything with them. And this single searcher isn’t alone, every other searcher needs to adopt this strategy to capture atomic MEV. The result is what we see reflected in the data: chains congested with spam and fees elevated by that spam.

The root causes of spam#

The spam congesting high-throughput chains isn’t an accident. It is the direct and rational response to a flaw in the market structure: to profitably read the latest state of a block and react to it, a searcher must blindly write a transaction within that same block.

The arbitrage bot we dissected is an example of this in action. An offchain query can fetch the state of the last-committed block, but this lags behind the MEV opportunities being created by transactions within the block currently being built.

On a network like Base or Solana, native mempools are private. This means that searchers have no visibility into user transactions being executed and the opportunities they create until the block has been published. The only way to both discover and capture the resulting arbitrage is to have their own transaction executed in the same block, immediately after the user's. If a searcher waits for the next block the opportunity is long gone already, captured by a competitor who seized the opportunity to capture it onchain.

The phenomenon of rampant onchain searching is due to the interplay of our different properties:

First, transaction expressivity. Unlike in traditional finance, where a trader submits a simple, static order (e.g., "buy at X price"), a searcher can create a transaction that acts as an onchain program. This allows a searcher to encode conditional logic that executes based on the state of the market at the very moment of its inclusion, enabling complex, reactive strategies that are impossible otherwise.

Second, a shift to private mempools. To protect users from frontrunning, most high-throughput chains have made their mempools private. Providing essential defense against frontrunning, this also blinds searchers to user orderflow. Unable to see and react to transactions before they are included in a block, searchers are forced to blindly probe for opportunities by leveraging the expressive transactions above to do their MEV searching onchain.

Three, cheap fees. Onchain searching is supercharged by low-cost blockspace. Searchers can afford to hammer every block with speculative transactions knowing that the profit from a single success will cover the cost of many, many failures. And as gas gets cheaper, searchers can express more complicated logic to pursue even more complex strategies.1

Finally, the lack of an efficient auction. Competition amongst searchers takes place in an environment with no formal way to express preference over transaction ordering. With no formal, direct way to bid for a specific transaction ordering in the block, competition defaults to a wasteful proxy: raw gas consumption. The primary way a searcher can improve their odds of winning is to consume more gas at more points in the block, thereby increasing their chances one will land in the right place.

When combined, these four factors effectively create a spam auction. This is a profoundly wasteful mechanism that incentivizes network congestion and poorly captures value from MEV. To quantify the true scale of the inefficiency created by spam, we turned to the data.

Findings#

Our analysis confirms that MEV driven spam imposes economic limits on scaling.

We classified spam by identifying transactions that make repeated DEX queries but transfer no tokens. This was a specific heuristic chosen to identify systematically wasteful backrunning arbitrage that could be done offchain but is being forced onchain. We implemented this heuristic both in Python tooling as well as Dune dashboards. For more detail on the methodology behind this data, see the appendix.

Our data analysis was limited to OP-Stack rollups only because of the availability of certain RPC methods necessary for our spam inspection tools. Data from the Ghost Logs team confirms our findings are relevant for Solana as well, and others have found evidence of spam on other Ethereum rollups like zksync and Arbitrum.

1 Spam is systemic and widespread#

First, the problem is systemic and widespread. An analysis of top OP-Stack rollups shows that spam is not an isolated issue but a dominant force across the ecosystem. On chains like Unichain, Base, and OP Mainnet spam has regularly consumed over 50% of all gas used. As a result, we can conclude that this is a structural consequence of the current market design, not a localized anomaly.

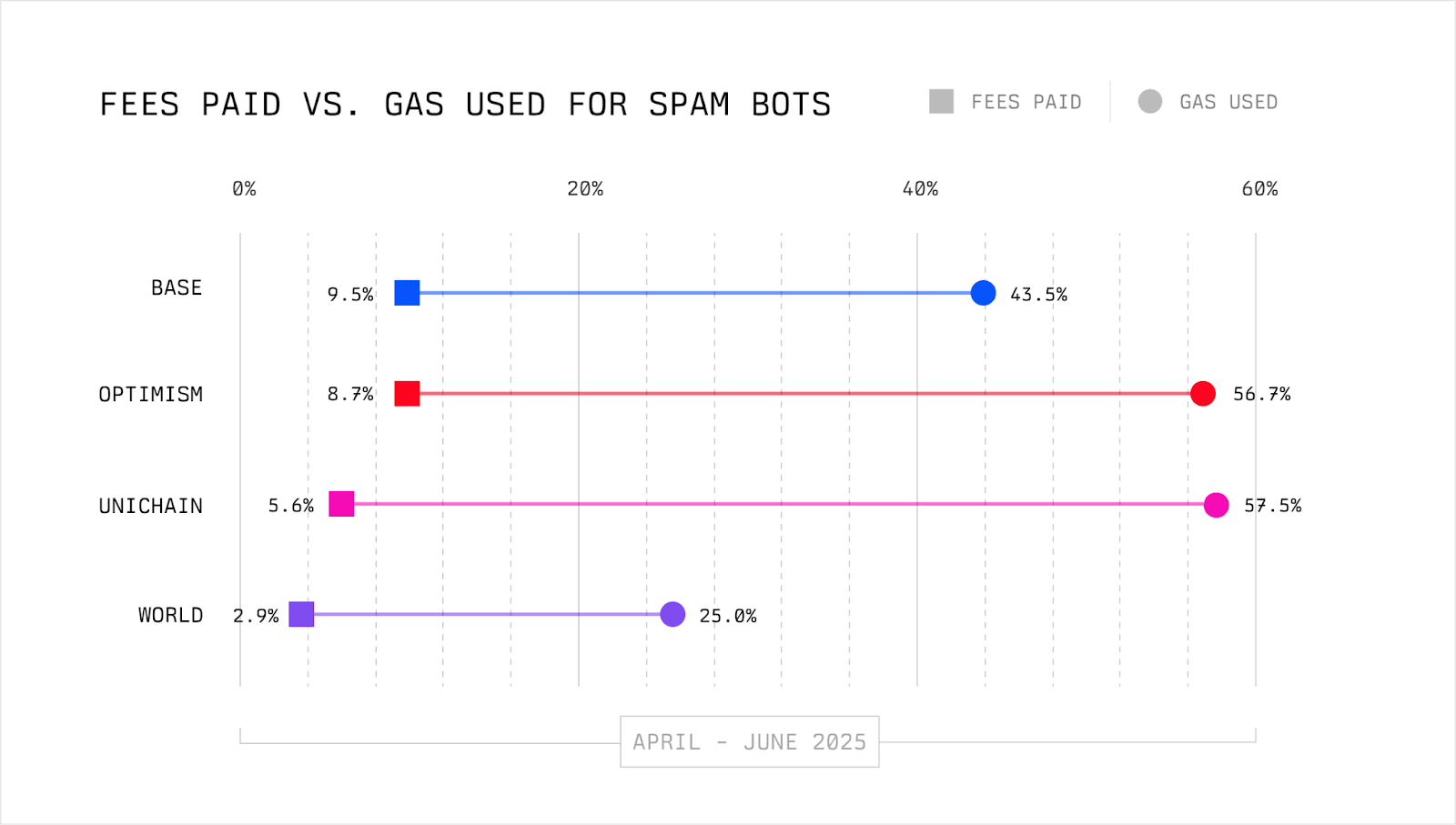

2 Spam consumes disproportionately more gas than it pays in fees#

Our second finding is that spam is extraordinarily inefficient from the chain's perspective.

Across the rollups we looked at, we find a huge gap between the resources spam consumes and the revenue it generates. Spam bots use amounts of gas that are multiples higher than the fees they pay relative to other users. As an example, spam bots on OP Mainnet used ~57% of gas but paid only ~9% of fees - a 6X multiple difference.

The gap between fees paid and gas used demonstrates that spam imposes massive external costs on networks while providing disproportionately little value in return, a hallmark of a systematically inefficient market. This includes the very real cost of wasted computation, as every full node is forced to execute these transactions, raising the hardware requirements for all network participants.

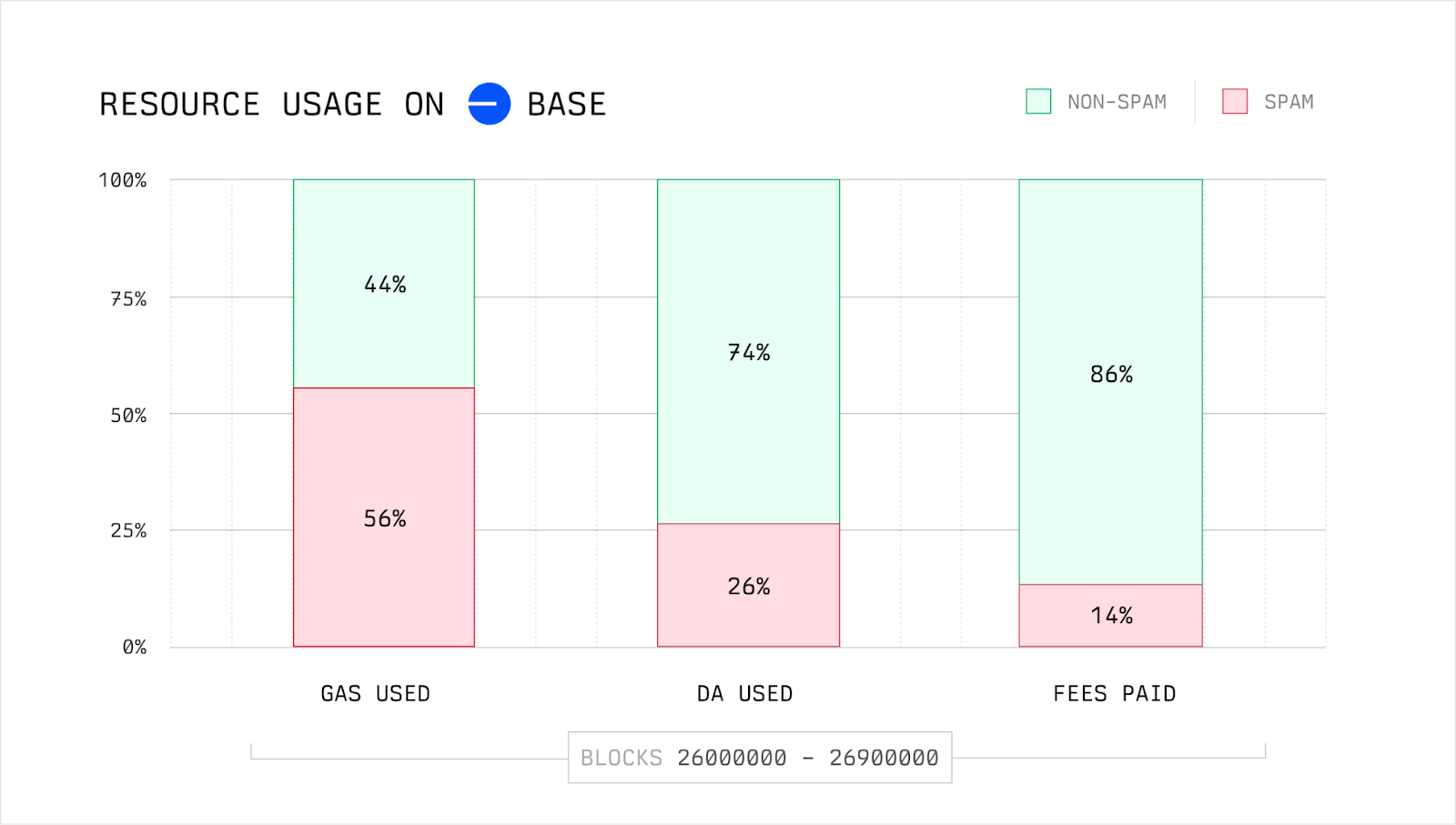

Further, we also analyzed how spam on L2s affected a rollup’s usage of L1 Data Availability.

We found that across a million blocks in February, spam bots on Base were responsible for approximately 56% of gas usage, 26% of L1 DA usage, and 14% of the chain’s fees. The % of DA usage by spam bots initially surprised us, but we found it correlates with the % of transactions by spam bots instead of gas usage. This makes sense because DA usage is a function of how well data compresses, not how much gas it uses.

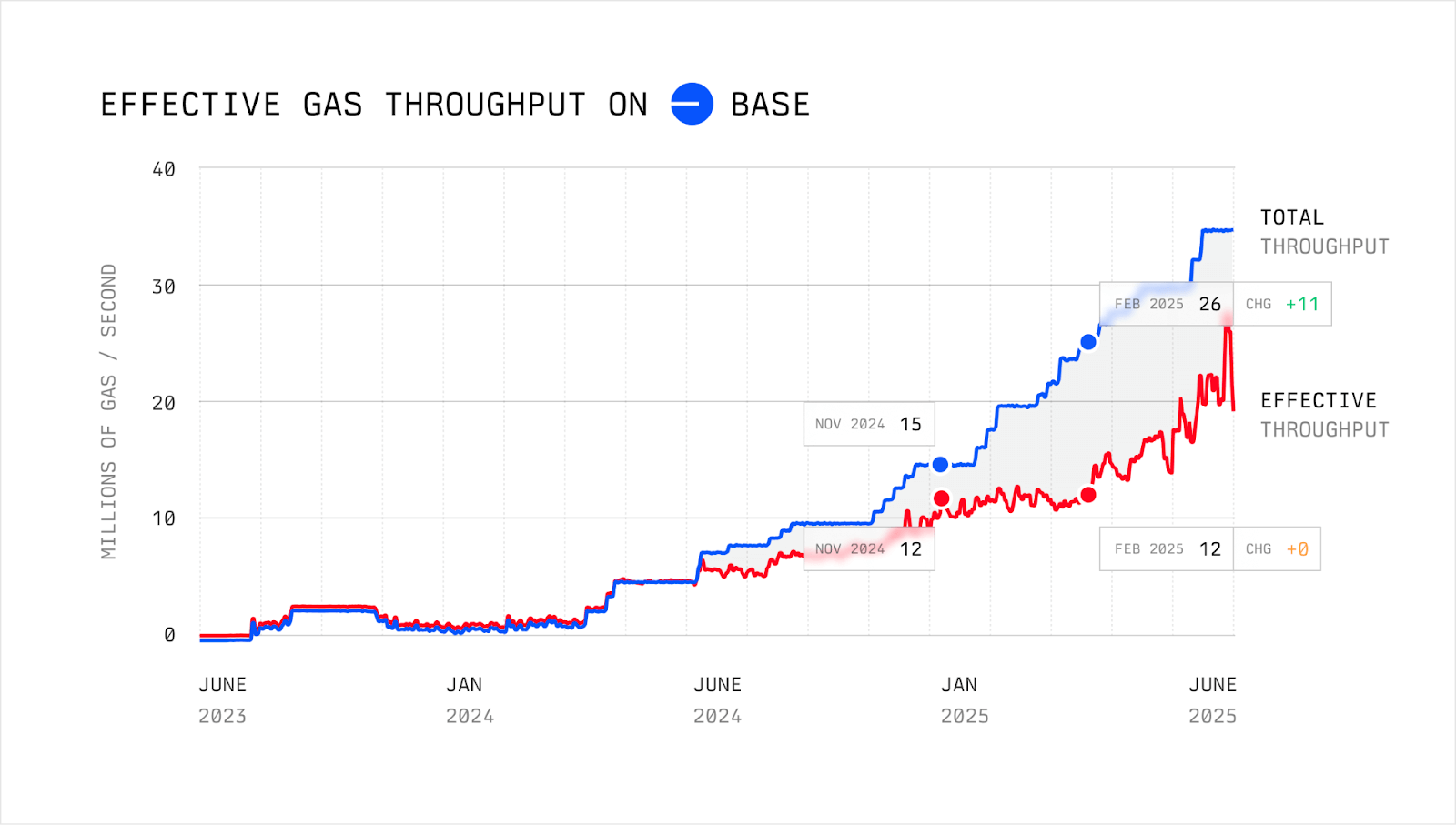

3 Spam limits and neutralizes the benefits of scaling#

Third, this inefficiency directly neutralizes the benefits of scaling. To measure the negative effect of spam, we introduce a new metric called effective gas throughput —the gas per second a rollup processes after deducting the gas used by spam bots.

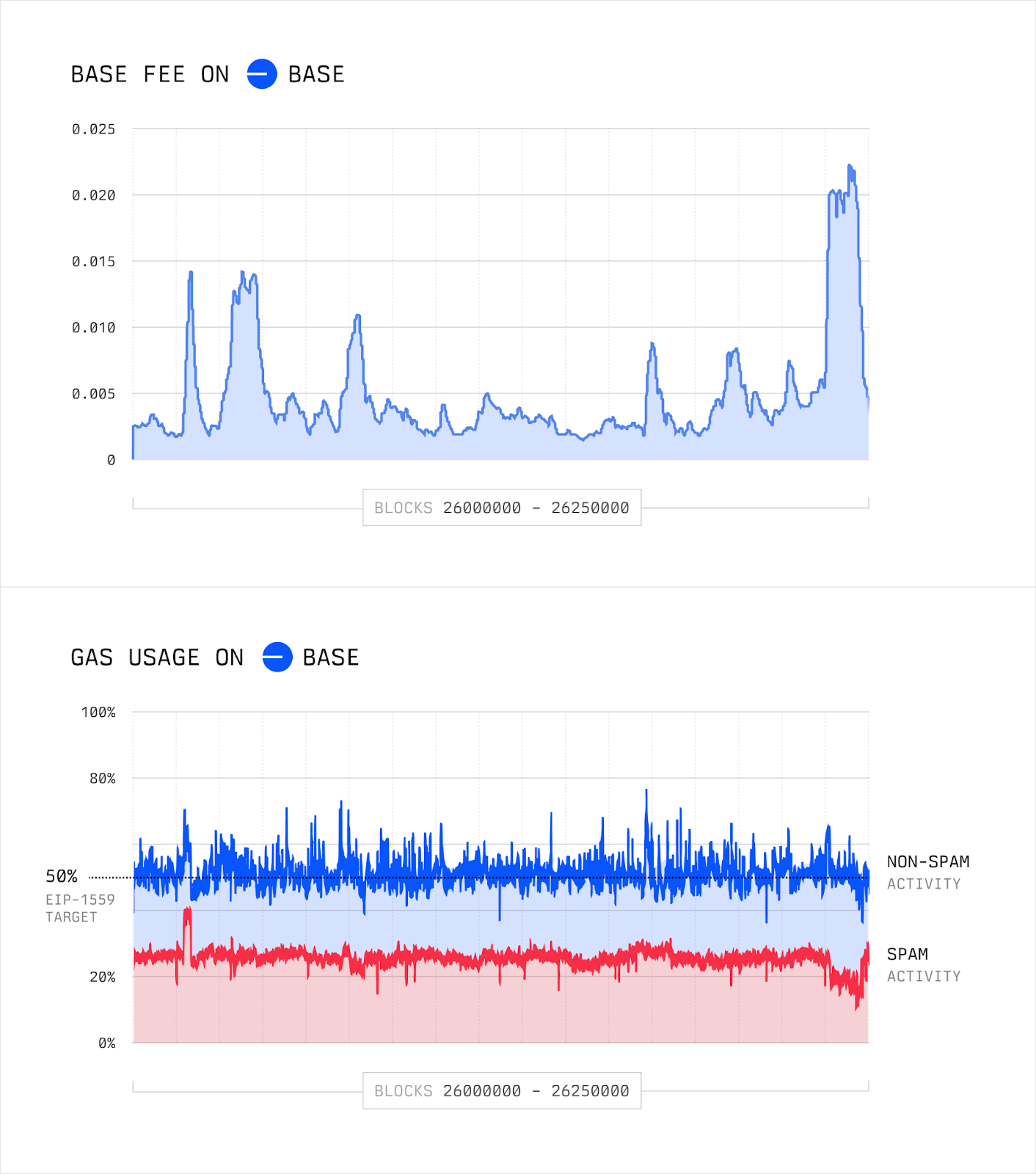

The trend on Base is stark: in November 2024, the overall gas throughput was 15 Mgas/s while the effective gas throughput for users was only 12 Mgas/s. Over the next four months, while the total gas throughput grew by another 11 Mgas/s, the effective gas throughput held roughly constant. Put another way, almost all new throughput was captured by spam.

Interestingly, after the end of February, there was a divergence and effective gas throughput started growing more closely with overall gas throughput. This appears to be tied to the amount of trading, and thereby MEV, in the market. The Libra scandal started on February 14th, and soon after effective gas throughput started to increase again. This correlates with the decrease in memecoin trading volume indicated by Telegram Bots trading volume.

4 Spam’s constant demand raises fees for users#

Perhaps the most direct impact on users is the persistent, artificially high baseline for transaction fees created by the constant presence of spam.

Scaling efforts on rollups have driven headline fees low enough that many organic users become price-insensitive (e.g. ~$0.01). Theoretically, with ample block space, price-insensitive users, and EIP-1559 fee market dynamics, fees should be driven towards their absolute minimum. The promise of scaling is to create so much capacity that this near-zero fee state becomes the norm.

In practice this is not what happens. MEV searchers trying to capture MEV with spam are flooding blocks with transactions and using up large amounts of gas. This activity pushes block usage up, and results in a stubbornly elevated base fee that reflects the systematically inefficient MEV market more than organic user demand.

Although fees are still low for end users, they are significantly higher than they need to be overall. That’s a problem because it means novel use cases that require abundant and cheap blockspace are being priced out, like onchain social networks or agentic micropayments.

5 The spam market is highly concentrated#

Finally, our analysis reveals that the searcher market for MEV spam is extremely concentrated.

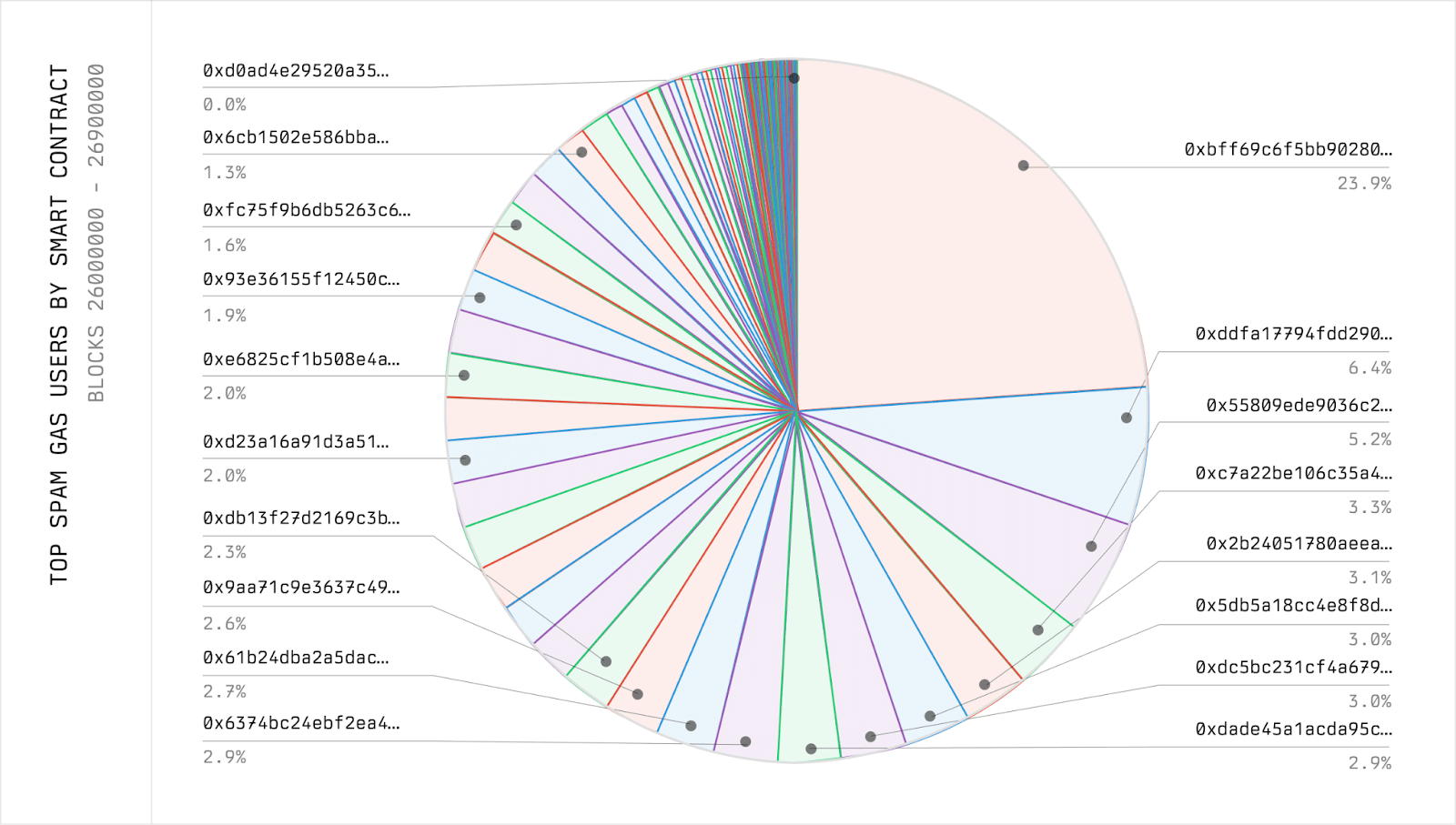

To examine this we looked at which smart contracts are using the most gas classified as spam across blocks 26000000 to 26900000. With an initial look, the market seems top heavy but fragmented.

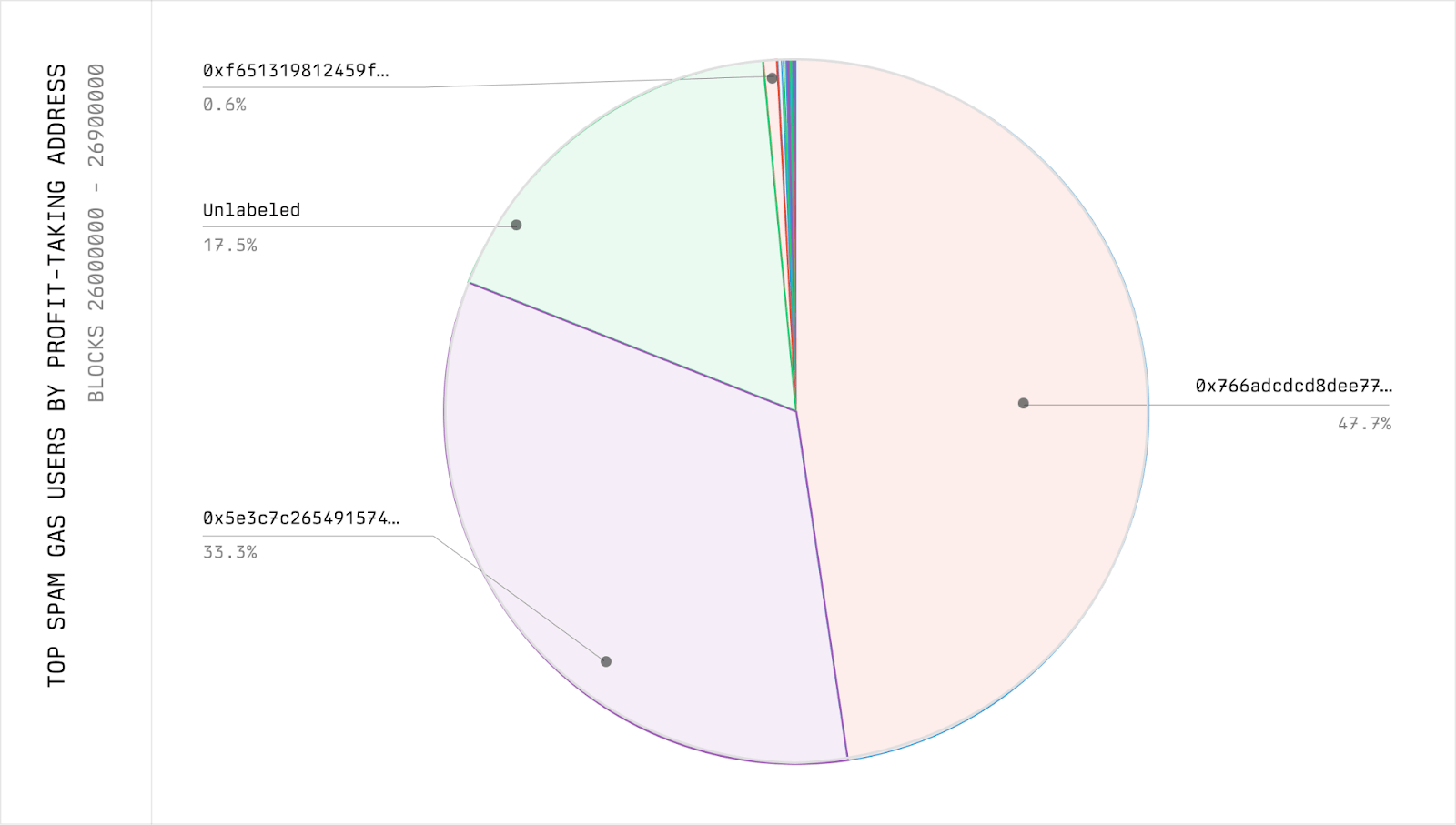

However, this view is misleading. Onchain analysis reveals that a common tactic is for searchers to rotate the smart contracts they use for spamming but to send profits to a consistent “profit-taking address” By tracing ETH transfers from successful arbitrage transactions we attempt to identify which smart contracts share the same operator. Not all bots use this method, but the top bots do.

When we group the data by profit taking addresses the market looks sharply more concentrated.

The result is stark, just two entities are responsible for over 80% of spam on Base. The extreme concentration shown suggests significant barriers to entry and that the current spam auction is not truly competitive. This lack of competition further blunts price discovery, meaning that the chain fails to capture the true value of the MEV being extracted, while also on top of suffering the externalities of spam.

The Path Forward#

We posit that blockchains should maximize how much useful economic activity they can fit in their limited blockspace.

By this measure, our findings show that today’s spam auctions are spectacularly wasteful: a two swap arbitrage on Uniswap v3 can take as little as ~200,000 gas, but the same economic outcome on Base consumes ~130 million gas.

Closing this ~650x efficiency gap is the key to unlocking the true potential of scaling.

To do so, we return to the four reasons why onchain searching became the dominant paradigm in the first place: transaction expressivity, mempool privacy, cheap fees, and lack of an efficient auction. We hold that cheap gas fees and expressivity are explicit goals of general-purpose smart contract chains2, and we want to lean into them.

Thus, the solution must be found in addressing the other two: allowing searchers to read upcoming state and express their preferences over it in a way that both upholds user guarantees and minimizes spam on the blockchain itself.

Toward the solution#

First, we will address state access through programmable privacy. An efficient market must provide searchers with real-time access to the transaction flow, while programmatically enforcing restrictions on how they can use that information.

The system needs to be able to verifiably guarantee that a searcher can only backrun transactions and can’t frontrun, sandwich, or leak private data. In turn, this visibility allows searchers to do their conditional execution logic offchain instead of doing so onchain. Once a searcher created a potentially profitable transaction offchain, they still need a way to land it in the precise spot to capture the MEV.

This brings us to the second component: we allow searchers to explicitly bid for transaction inclusion and ordering in an auction. Instead of a wasteful “spam auction” that competes on raw gas usage, an explicit auction allows searchers to submit a direct, monetary bid for the specific ordering right they are interested in.

These two components, programmable privacy and explicit bidding, work in tandem to create the solution:

- Programmable privacy eliminates the need to write to the chain to read the latest state, without exposing users to frontrunning.

- Explicit bidding provides an efficient, price-based mechanism to capture the value that controlled visibility reveals.

Flashbots has been experimenting with Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) to give searchers visibility without the ability to sandwich. TEEs give guarantees that specific code is being executed with data that is kept confidential even from the machine’s operator.

That allows for the running of searchers inside of TEEs where they are verifiably allowed to backrun private transactions, but aren’t allowed to sandwich or export any private data. We have proven this out on Ethereum L1, where searchers have been backrunning transactions in a similar system for several months now, and are actively adapting it for L2.

Conclusion#

The conversation around scaling has been narrowly focused on raw technical throughput for too long. Our findings show that the critical frontier is no longer making blocks bigger. It is using blockspace more efficiently.3

That is because for every extra unit of blockspace freed up, MEV incentivizes spam to consume the new capacity. In other words, a substantial portion of the benefits of “scaling” are absorbed by economically rational MEV bots, preventing those gains from being felt by real users. This is a problem today because it is pushing up fees for regular users, limiting scaling efforts, and wasting vast network resources.

Therein lie the limits of scaling: increasing blockspace capacity leads to more throughput, but their effect on fees is limited because increasingly expressive onchain MEV eats up most of the gains.

To break through these limits and unlock the true potential of scaling we must transition away from wasteful spam markets. With programmable privacy and explicit bidding, we eliminate the incentive for spam and replace wasteful "spam auctions" with an expressive, fair, and efficient market for MEV.

Adoption of MEV auctions is not a luxury but a strategic imperative. The key is to use TEEs to give searchers access to transaction flow, but programmatically restrict how they can use it. This design achieves the ideal outcome: it enables backrunning arbitrage without spam while preventing sandwiching.

For chains, this means capturing more revenue in an efficient, spam-free market. For users and builders, the full benefits of scaling are finally realized through lower, stable fees and genuine capacity.

What might be possible when we break through the limits imposed by spam? What gets unlocked when transactions are almost too cheap to meter? What new types of applications will be created?

There’s only one way to find out.

Collaborate with us#

We are actively designing and building this future for rollups. Come and talk to us if you want to push past economic limits and innovate onchain market design together. You can DM dmarz or myself on Twitter.

Thank you to DataAlways, Hasu, Fahim, Danning, dmarz, Nathan, Georgios, Dan, buffalu, Quintus, Tesa, Anika, Brian, Xin, Sam, Eli, Christine, Christoph, Alex, Fred, and many others for their helpful comments. A special thanks goes to Phil. And thanks to Achal for the design help.

Appendix#

Spam identification heuristics

To identify what transactions were spam or not we used two heuristics:

- No token transfers: Does the transaction transfer any tokens? If so, it is not classified as spam.

- Repetitive DEX Price Queries: If a transaction queries common DEX price feeds at least four times without resulting in a token transfer, it is classified as spam.

We believe that these heuristics are robust as of the time of writing. Doing anything with tokens is an indicator that the transaction was generally useful to someone. Spam won’t transfer any tokens unless an MEV opportunity is found and executed. Moreover, the DEX price query heuristic effectively identifies bots systematically checking for arbitrage opportunities, which is the primary form of spam we’ve seen. Finally, this definition of spam accounts for the wasteful activity of only checking onchain for dex prices, but excludes the productivity activity of backrunning.

However, this definition needs to be made more robust going forward. It would be trivial for spam bots to game this by transferring tokens. How to classify what is “spam” or not is an exciting area for follow-up research. Moreover, this definition notably captures blind backrunning arbitrage bots which make up the majority of MEV, but omits other forms of MEV strategies like liquidations.

Spam identification methodology

To identify spam activity, we examined transaction’s traces. For each transaction, we looked at each of their traces to determine whether it invokes a token transfer function or a dex price function (such as slot0(), getReserves(), etc.). If the transaction transfers any token then it would not be classified as spam. However, if it transfers no tokens and it makes 4 calls to get DEX prices, then we classify it as spam.

We chose 4 to be conservative but experimented with setting a threshold of 3 calls instead of 4 and found it to have little impact overall. Similarly, we used transfer events to filter out transactions with transfers on Dune, but found that to similarly not have a large difference relative to using traces.

spam-inspect

To investigate spam, we created spam-inspect - a Python tool built for analyzing Ethereum rollup activity to identify spamming bot activity built with performance in mind. spam-inspect works by tracing each transaction in a block and using those traces to apply the above heuristics.

This requires the trace_block method. At the time of writing, that method is only available on OP-Stack chains where OP-Reth or OP-Erigon can run.

Dune queries

We built Dune materialized views that identified transaction hashes which meet the above criteria by filtering out transactions which have a Transfer event, and looking for repeated DEX price calls. This slightly differs from spam-inspect in that it relies on Transfer events rather than traces. These materialized views of spam transactions were used to build follow-on queries.

DA estimation

Although this article is mostly about how spam affects gas, it also affects other resource usage, like L1 data availability that rollups use. To derive an estimate of the amount of L1 DA that spam on L2s waste we built a custom data pipeline that reused parts of op-batcher. To arrive at our DA estimate we ran two calculations:

- What is the total size of a block when compressed with all of its transactions?

- What is the total size of a block when compressed but with spam removed?

The difference between these two is taken to be an estimate of the amount of DA per block that spam uses.

1 This suggests that the MEV usage of a chain will continue to scale with its throughput

2 The logic can be different for an app-specific chain - deliberately restricting transaction expressivity can be a valid strategy here

3 Explicit auctions solve the problem of systematically inefficient resource usage but they introduce a different limit: the time required to run a fair and competitive auction. This time imposes a lower bound on block times due to networking latency and the computation needed to run an auction. These combined latencies mean that an efficient auction requires a minimum block time, and suggests a tradeoff between maximizing usage of block space and minimizing block times. An article on this is forthcoming.