Tl;dr The first article of this series outlined the threat that exclusive order flow (EOF) poses to the builder market. This article argues that order flow auctions can address part of the EOF problem and explores meaningful differences between two auction design types, while identifying similarities that point to a more fundamental problem.

For discussions on this post, see here.

Note: I use “extractor” to refer to both searchers and builders and “order” to refer to any kind of message that allows for permutation of Ethereum’s state (e.g. a standard transaction).

Order flow auctions#

In many cases, extraction of MEV requires a user’s order to be executed on chain. In these cases, execution of the user order exposes a blockchain state that can be profitably acted upon by an extractor. Backruns and sandwiches are common some examples. In PoW, the miner was put in the driver’s seat because it was ultimately the miner that decided the conditions under which these orders were to be executed. Competition between searchers led to the formation of an auction in which searchers paid the miner to execute their bundles in place of their competitors’ since the miner had this decision-making power. What has thus far been widely overlooked is that the execution of a user order also requires the user to submit this order. The dependence of value extraction on the user should tell us that the user is in a negotiating position comparable to that of the miner (or validator). One way to capitalise on the user’s seemingly powerful position is to run an auction “facing the other way” in the MEV supply chain. In other words, the situation can be flipped so that extractors offer bids to users to execute their order. This would change the value flow in the MEV supply chain in favour of the end users. If built well, it could additionally prevent rent-seeking by channeling value out of the hands of extractors, reducing the rewards block builders can use to influence proposers (see crlist example in part 1. Additionally, this value redirection could provide wallets with a way to monetise (an alternative to payment for order flow). Incentives are hard and the MEV ecosystem complex, but the combination of all of these factors, which are already valuable in isolation, should culminate in a world that is more robust to the threat of EOF - at least, that is, if you buy the argument in the previous article.

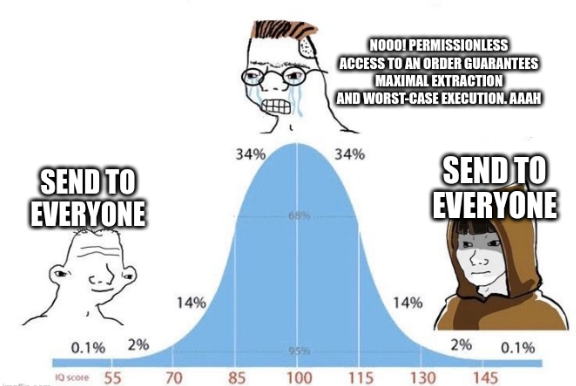

Option 1: explicit auction#

The idea here is to implement an auction designed in the shape of the most natural notion of “auction.” The user withholds permission to execute their order for a period of time (e.g. 2-3 seconds) while exposing enough information about the order for extractors to estimate the value of the order. Extractors enter in a bidding war that sees the winner being given permission to execute an order (e.g. by receiving a signature).

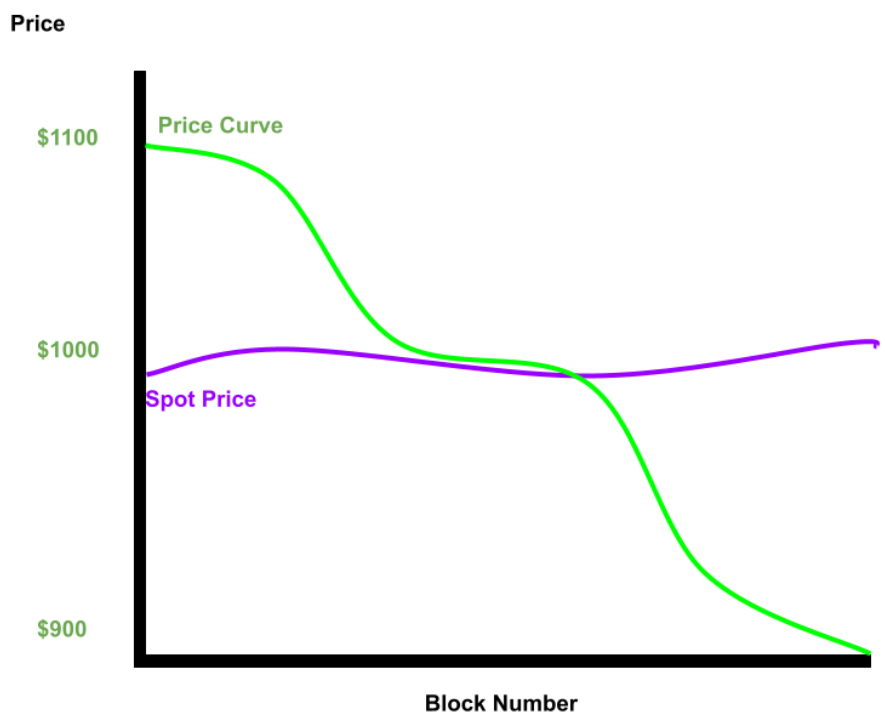

Under perfect competition, one would expect bids to approach where is the value of the opportunity exposed by this order and the cost of inclusion likely arises from bidding to builders for the execution of the subsequent bundle (in abstract terms, one can think of the cost of inclusion as the validator’s cut). Since only a single extractor would have control over the opportunity (no competition), that extractor presumably would not have to pay much for inclusion in a block, meaning most value flows back to the user.

Of course, it is unrealistic to expect users to carry out this auction on their own. Instead, users would have to route orders to an order flow auction platform. In fact, versions of this kind of auction already exist in the form of Rook and various RFQ systems:

- Rook has a similar design to what is described above, with extractor payment denominated in a numeraire (soon to be WETH).

- RFQ systems have market makers compete to offer the best possible rates on a trade. Effectively, this amounts to executing a market order.

If you squint a little, the two systems are doing the same thing. If Rook allowed users to specify the asset they were being compensated in as the asset they were trading into, then there wouldn’t be much that separates the designs at a high-level. In the details, however, there are important differences. RFQ’s only support orders of a certain format (market orders), while the ideal auction would be completely general. This generality is desirable because of the difficulty of knowing which orders bear MEV. Bids being denominated in a single numeraire also simplifies things for the extractor leading to higher user payments, albeit a potential inconvenience for the user as well. Irrespective of their individual differences, both RFQ’s and Rook represent important efforts in testing the feasibility of explicit auctions.

Aside: 💡 An interesting secondary benefit of auctioning off the permission to execute an order is that a winning searcher should be able to detect bundle theft from builders very easily. Any competition for the inclusion of a bundle based on an order won in the OF auction is clearly the result of theft (assuming a functioning auction). This could mean that searchers’ incentive to restrict their bundle submission to only a handful of dominant builders is greatly reduced.

The two main challenges of designing an explicit auction is avoiding a trusted auctioneer and achieving both low-latency guarantees and high value-capture. As far as I’m aware, all current designs are centralised and there aren’t any public proposals for a decentralised or cryptographically secure explicit auction. In current designs, the auctioneer is placed in a powerful position, which leaves the door open to abuses like siphoning off user funds by manipulating the auction in exchange for side payments from extractors. Further research into the feasibility of efficient trust-minimised explicit auctions is much needed.

Auctioning off permission to a single extractor has the downside that execution depends on a single party. Order may not be executed because, for instance, an extractor overbids in the user auction (it may be hard to estimate total value or how much an inclusion bid would require) or bids for an order with no intention of executing it simply to grief competitors. The auctioneer could restart the auction, incurring a further latency penalty, or have the order executed through some other means like a public mempool, presumably surrendering value. In designing the auction, one should attempt to minimise these latency costs by introducing some sort of (dis)incentives. Rook, for example, is building out a reputation system in an attempt to handle this. Another, harsher mechanism would be requiring unconditional bids from extractors so that extractors who place winning bids pay their bids irrespective of whether they execute the order. Execution enforcement mechanisms, however, do not come without a cost.

One knock-on effect of having a good mechanism for enforcing execution of orders is that builders would likely be unable to acquire order flow via the auction without sharing that flow with other builders. In other words, the pressure to ensure execution will mean that bidders in the auction will likely attempt to execute the order by submitting bundles to multiple builders. The consequence is a fragmentation of the MEV extraction process which introduces inefficiency. Because the order flow auction is carried out by agents without knowledge of the exact state that an opportunity will be executed on, the valuation of a user order in the order flow auction will only ever be an approximation of that order’s end value. This likely results in extractors underbidding for user orders so as to avoid overbidding and having to either lose money on executing the order or be punished by the enforcement mechanism. There are also other questions that a good implementation must answer like how extractors should bid for multiple orders that are to be used in one extraction opportunity.

Option 2: fee escalator#

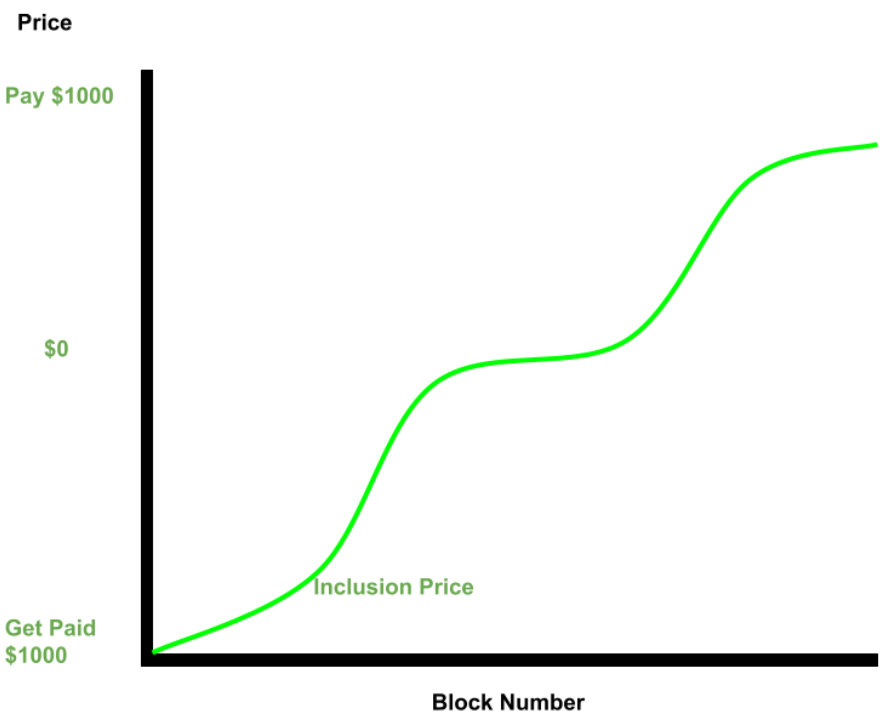

If a user knew the exact MEV of their order, they could set the price of execution of their order as and reclaim almost all of the order’s value (the assumption here is that takes gas cost and other orders in the mempool into account and that inclusion cost can be 0 as builders can dictate inclusion). Users, unfortunately, don’t know how much their orders are worth, but the value of their order can be approximated using a dynamically changing price as part of the validity conditions of the order.

The notion of fee escalators isn’t new. Fee escalators were originally proposed as a way of improving the first price auction for transaction inclusion that was common before EIP1559. The original proposal wasn’t focused on MEV extraction. Here fee escalators are presented as way for the user to carry out an implicit Dutch auction in a permissionless way, precisely with the aim of MEV capture. Instead of the user auctioning off permission to execute an order, the auction is baked into the order itself so that the order can be sent freely into the world without requiring any permissioned middlemen.

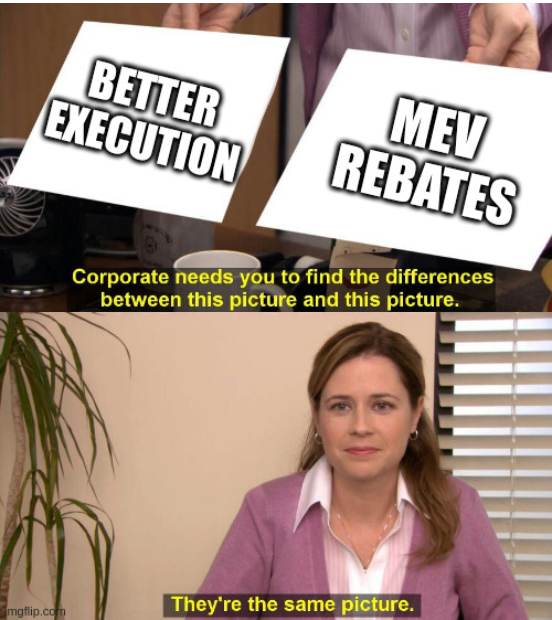

The rough idea is to have some sort of fee that changes as a function of time and is hardcoded into the order. The obvious example would be a kind of gas fee that escalates with time. If the gas fee is set to be less than the base fee then the user is effectively requiring payment for their order in the form of a gas discount. Importantly, the fee should be allowed to be negative to allow for payments larger than the basefee. Such payment could come in the form of a total gas discount (i.e. the user’s gas is paid for them) and a direct payment. Once the fee escalates to whatever the basefee is, execution is effectively guaranteed. Users can also set a timeout parameter so that orders aren’t valid after a certain time to avoid unbounded fees.

Thanks to Scott Bigelow for the diagram

There need not be many restrictions on what kinds of curves can be set. One can imagine a price that doesn’t change for blocks and then suddenly jumps, an exponential curve or a straight line. Just like with Rook and RFQ’s, the idea of rebates can also be translated into better execution by changing the unit the fee is charged in. One can imagine a limit order with a dynamically increasing price (or slippage). Similar to when a fee is used, once the price given by the curve passes the “true price” the order will undoubtedly be executed.

The main selling point of fee escalators is that they allow us to avoid a trusted auctioneer or having to construct a decentralised version of such an auction. Some of the inefficiencies with explicit auctions are also avoided. The griefing attacks mentioned above are no longer viable and the auction for MEV extraction happens in a setting where the size of the payment to the user can be conditioned on both the state on which execution is happening and whether the opportunity is executed. This means that if the implicit price (difference between gas fee and base fee) is lower than the value of the order at the time of block production, one can expect the order to be executed in that block.

The main selling point of fee escalators is that they allow us to avoid a trusted auctioneer or having to construct a decentralised version of such an auction. Some of the inefficiencies with explicit auctions are also avoided. The griefing attacks mentioned above are no longer viable and the auction for MEV extraction happens in a setting where the size of the payment to the user can be conditioned on both the state on which execution is happening and whether the opportunity is executed. This means that if the implicit price (difference between gas fee and base fee) is lower than the value of the order at the time of block production, one can expect the order to be executed in that block.

Fee escalators, however, are not free from inefficiencies themselves as curves are hard to set. There are two challenges in setting fee curves. The first is that, although curves are very expressive, it is hard to translate user preferences into these curves. Most users simply want to click a button and maybe adjust a slider at most. Fortunately, this can be addressed by wallets or DApp UI’s abstracting away the curve setting process. The second challenge in setting a fee curve is that, just like before, one cannot know the exact value of an order as one does not know the state that it will be executed on. The user needs to guess how to set the curve correctly so that it closely approximates the value of the order on whatever state it ends up being executed on.

Another consideration is that implementing fee escalators would require DApps, wallets and users to play together and incur the overhead of including a new order type. The mempool also currently doesn’t support order formats outside standard transaction formats so users would have to forward their orders to different private mempools or routing services, until this changes (not a guaranteed outcome). One way to address this issue and motivate switching cost of this scale is to lump a bunch of features together. Changing transaction format is also a requirement for account abstraction (AA) so the new order format can be designed to kill both the AA and the fee-escalator birds with a single order-standard stone. It may even be possible for this all to be done without any core protocol changes a la EIP712.

Inefficiencies: time and value#

The arguments above highlight inefficiencies in both the first-price and the Dutch auctions. The analysis suggests that both designs have in common the shortcoming of decision-making with incomplete information - in first case for the extractor, in the second for the user. They also share a property that the inefficiencies can manifest in either added latency or reduced value extraction.

In the case of the explicit (first-price) auction, extractors may overbid increasing the chance that the extractor exercises last look privileges, leading to an increased expected latency. Extractors may also underbid, meaning users are compensated less. One might expect the inefficiency to come largely in the form of latency when the execution enforcement isn’t very strict and mostly in the form of lower payments in the presence of a strict mechanism.

In the case of the fee curve (Dutch) auction, users must approximate the correct curve. Starting the fee curve too low and not steep enough would mean that the order takes a very long time to execute. Starting the curve too high means the order is likely to be executed quickly, but the user is not compensated the full value of execution. This problem is exacerbated by Ethereum’s slow block time. Slow block time means that a gentle curve that’s set slightly too high takes a long time to find a price for execution, increasing the incentive to have a steep, low-resolution curve leading to a loss of value. A possible mitigation to this is incorporating a different domain with a notion of time that is of a finer granularity (e.g. see decentralised builder idea). Of course, this brings on its own host of challenges and deserves a separate post.

A slide from Phil Daian’s presentation at SBC

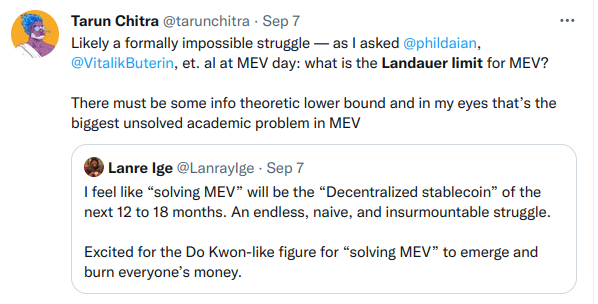

To be clear, the arguments above still see both designs provide a significant improvement over the status quo. It is in comparing these designs with an intuitive notion of optimality, however, when it appears there is some inherent cost to the user. This cost seemingly materialises as a combination of latency and loss of user value where the degree to which this loss appears in one form or another is a function of the parameters of the auction. Finding the appropriate metric to measure cost across latency and value destruction and establishing a lower bound on this cost are interesting open research directions, which would serve the larger research question at hand: is the cost described above inherent to blockchain? (a proof by construction would be highly desirable here).

Aside: 💡 Privacy It’s no secret that having more information on what’s going to happen next is a huge advantage in markets (and potentially other areas). This is already widely understood in TradFi, but hasn’t really been taken into account in the paragraphs above. Not only could the aggregate directional information of order flow be valuable, the informational context in which an order is executed plays a role in its value (e.g. whether a big swap is publicly know and priced in on CEX’s should affect its value). Toying with privacy and capturing information value is a complex topic and should be explored in its own post.

What does this accomplish?#

This post represents the meeting of two goals. There has long been a push to minimise the value captured from users in the form of MEV and there is now a need to address the dangers of exclusive order flow. The way in which order flow auctions serve to minimise user MEV exposure is obvious. This shift of value back to the user, should mean builders have less valuable blocks with which they can shape validator incentives. Value flowing back to the user could also provide a way for wallets to monetise order flow outside of harmful PFOF. Admittedly, this monetisation has been underspecified in this article. The high-level idea would be for wallets to take a cut of the value flowing back to the user, bringing into closer alignment the incentives of the wallet and the user.

There is also a third goal that has implicitly been addressed. A growing topic of research interest is a general or fundamental theory of MEV. In pursuit of an effective order flow auction, we illuminate more characteristics of the nature of MEV. Work in understanding and developing an order flow auction will hopefully not only help us to achieve the goals of MEV minimisation and PBS health, but also serve as stimulus driving forward the understanding of MEV. The exploration of this bit of landscape can only contribute to the completion of a map.*

* fortunately for us, @sxysun1 has been thinking about some of the theoretical questions raised in this article for quite a while now 👀

A big thanks to @0x81b, Bert Miller and Alejo Salles for providing helpful feedback in writing this post.

Appendix for researchers#

Research direction: In this article, there is a tacit assumption that those who include inclusion in a block (presumably builders) will comply with the sequential nature of the game and only capture whatever value is left on the table after the order flow auction. There are, of course, other courses of action available to the agent in control of inclusion. A monopoly over inclusion (imagine a single builder/validator) could mean that the monopolist is able to reject any extraction of utility that doesn’t pay a certain fraction of extracted utility to the monopolist. In the iterated game, this could yield increased payoffs depending on the ability of the monopolist to asses the utility of extractors.

If inclusion is not monopolised (e.g. competitive PBS or, validators competing across time), it might be the case that the sequence of auctions is important in determining where value flows. If the value of the inclusion is determined first somehow, it may be that users can only internalise what’s left on the table in a mirror image to the situation described in this article. (This doesn’t seem like it should be an exactly mirrored outcome because there is still information asymmetry in favour of the user).m

There is also the question of what can be achieved when sequential auctions are dropped completely (if possible). In other words, the designs explored in this article feature two auctions, with the first executed without “full information.” Is it possible to design a single incentive-compatible, credible auction that takes into account more information? If so, is there some sense in which inefficiency is minimised? Who walks away with the majority of rewards? Note: order flow auctions isn’t the only place where these research areas are of interest.

These are the questions I’ll be spending my time on 🙂