This post is part of a Flashbots research series exploring how decentralized blockbuilding connects Ethereum's scaling and privacy roadmap to real-world execution.

tl;dr: this post introduces Flashnet, a new anonymous broadcast protocol with much lower latency than existing alternatives. We plan to deploy Flashnet both (1) as a user-facing censorship resistance and anonymity tool that complements onchain privacy solutions and censorship resistance mechanisms like FOCIL; and (2) as a means to connect actors along the block building pipeline, moving BuilderNet closer to permissionlessness and the SUAVE vision. Flashnet is the event horizon for distributed block building — the signal passes through, the sender disappears.

Introduction#

Privacy is one of the few properties that unites very different constituencies in the Ethereum ecosystem. Cypherpunks care about it as a matter of personal safety, autonomy and censorship resistance. Product builders and protocol designers care about it because information asymmetries shape market structure. In both cases, privacy is not a cosmetic feature, it determines who can participate in the system, under what conditions, and with what risks. In this light, we are excited to introduce Flashnet, a new low-latency anonymous broadcast protocol.

Ethereum has made meaningful progress on privacy. PSE's Ethereum Privacy Roadmap usefully divides the problem into private reads (querying state) and private writes (submitting transactions). Private reads are being addressed with TEE-based RPCs in the short term and cryptographic techniques over time. Private writes have advanced through stealth addresses and shielded pools like Railgun and Privacy Pools, which significantly reduce onchain linkability.

While "reads" and "writes" are terms that (rightly) model Ethereum as a database, blockbuilding models Ethereum as a distributed execution pipeline that writes to this database. Privacy failures occur not only in state accesses, but in how information flows through this pipeline during execution. Even if transaction contents are hidden, the identity of the transaction sender may not be. Simply using a mixer like Railgun or Privacy Pools does not prevent attackers form tracking your metadata (e.g. IP), connecting your accounts, and tracking your identity and location. It also doesn't prevent censorship or frontrunning based on this information. The missing property is network anonymity.

Flashnet provides exactly this property. The protocol can serve both as a user-facing anonymity and censorship-resistance tool for transaction submission and account abstraction mempools, and as a coordination primitive for permissionless block building.

Anonymity In Block Building#

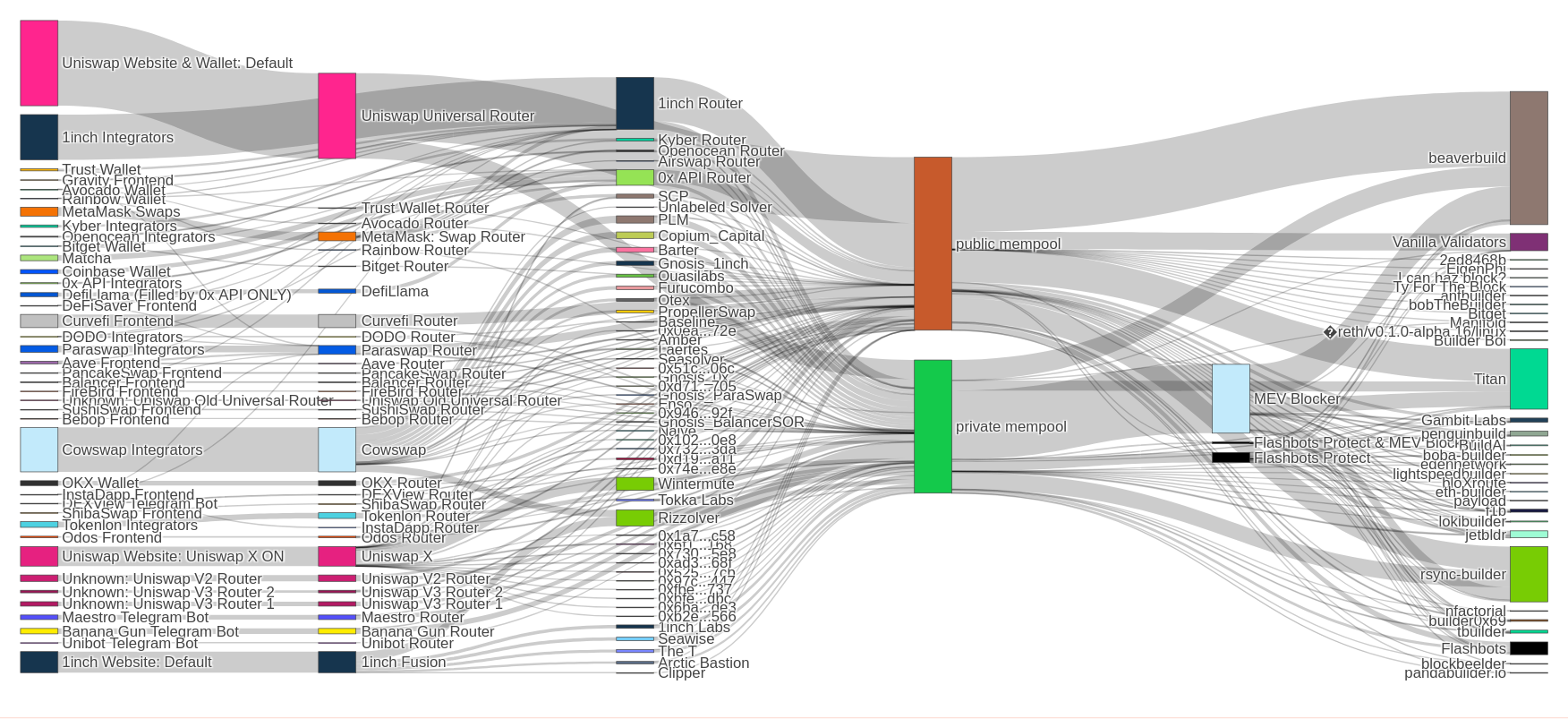

A look into Ethereum's execution pipeline from orderflow.art

Three years ago, we announced SUAVE, our vision for a decentralized block building supply chain that unbundles the block building role. At the time, block building was not only centralized, there was little means to hide transaction contents from block builders and no anonymity solution that did not compromise on the desired latency. After a lot of research into privacy primitives (SGX, MPC, FHE, TDX), we launched BuilderNet, introducing new privacy and verifiability guarantees and taking our first step in realizing our vision.

Adding these guarantees isn't purely attractive because they align with cypherpunk ideals. As we explain in our recent post, decentralized building: wat do, we see strong privacy tooling as a necessary condition for the success of DeFi. The execution path of DeFi transactions typically involves many actors - order flow auctions, solvers, relays, builders, validators - and execution quality depends on interactions between them. As we develop our ability to share sensitive information without risking abuse, blockchain execution pipelines will be able to incorporate more counterparties, more strategies and more information, benefiting both decentralization and execution quality.

So far we have only taken the first step. Even when infrastructure runs in TEEs, operators are still able to learn metadata opening up surface area for selective censorship and adversarial MEV strategies. Existing anonymity solutions, such as TOR and Nym, require users to choose between weak anonymity or high latency. Similarly, FOCIL promises to add censorship resistance but only at the cost of higher latency and required use of the public mempool which invites frontrunning and other undesirable forms of MEV. These tradeoffs can be impractical for a lot of use cases.

For simple transfers, high latency simply means bad UX relative to unprotected designs. This may not sound like that big of a deal but more usage means stronger anonymity for the users who need it most. For DeFi and other use cases that touch contentious state, outcomes depend heavily on other transactions (e.g. swaps on the same DEX) and millisecond price movements on centralized exchanges. For these use cases, latency can translate to money lost or prevent participation altogether. As we drive down latency overheads, the same anonymous broadcast primitive that protects a Railgun user from metadata-based deanonymization can also prevent block builders or intermediaries from filtering or disadvantaging participants based on network identity, and deliver blocks to validators.

Today, BuilderNet blocks are being built by Flashbots, beaverbuild and Nethermind, because we are able to verify that these nodes are running the appropriate privacy-preserving software in a secure environment. Our next planned architecture modularizes and distributes block building across a larger set of specialized actors. Incorporating Flashnet is one of the steps to getting there - a key piece to letting anyone run a node and scaling BuilderNet beyond the limitations of reputation and trust.

Anonymity vs. Latency vs. Bandwidth#

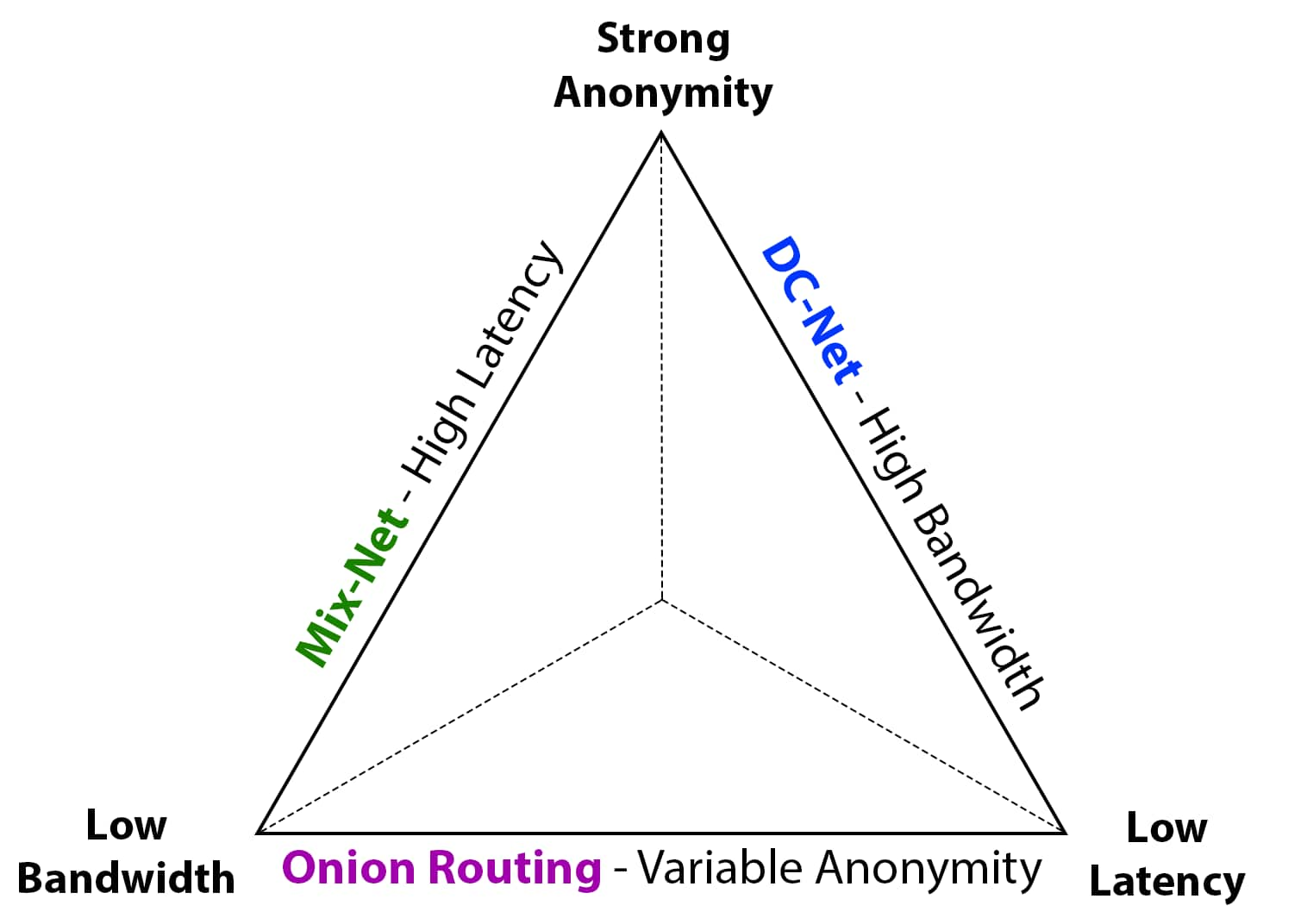

When building anonymous broadcast channels, three metrics are of key importance: anonymity, latency, and bandwidth.

Anonymity measures how hard it would be for an external (network-level) observer to discern the sender of any one message published by the anonymous broadcast system. In practice, this is often quantified by the size of the anonymity set: the number of plausible senders for a given message.

Latency measures how long it takes for messages to be delivered and, as explained above, we would like latency to be as low as possible.

Bandwidth measures how much data needs to be sent and processed by the system. Even if few users send meaningful messages, we need many users to provide "cover traffic" to provide good anonymity for everyone. For this reason, the bandwidth overhead of the system is not just comprised of the actually sent messages, but also of the amount of cover traffic that is needed for anonymity.

In the ideal world, we would like anonymity to be maximised, while latency and bandwidth overheads are at a minimum. In reality, however, there is no free lunch and often one has to pay a price in at least one metric. After all, what is a blockchain post without a trilemma?

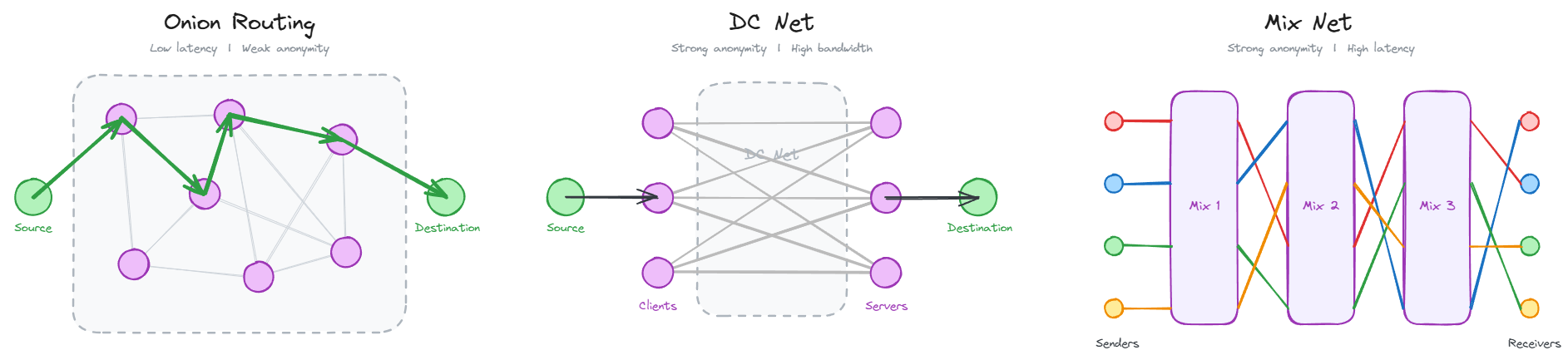

Several well-established blueprints exist that are worth revisiting here shortly:

Onion routing, famously employed by the TOR network, is highly efficient in terms of bandwidth overhead and allows each client to asynchronously decide when to send their message. In practice, it can also achieve low latency, but at the cost of weak anonymity against adversarial network-level observers.

Mix-Nets, such as Nym, achieve stronger anonymity against global passive adversaries. They rely on cover traffic, and batching and reordering of messages, which introduces delays. The result is increased end-to-end latency and higher bandwidth overhead compared to low-latency networks.

DC-Nets ("Dining Cryptographers" Nets) are different from relay-based designs like TOR and Nym. Instead of routing messages through several machines on the network, participants simultaneously contribute to a shared computation that reveals a batch of messages without linking sender to message. DC-Nets can provide strong sender anonymity with moderate latency in synchronous settings, but typically at the cost of higher bandwidth and computational overheads.

Since anonymity is derived from cover traffic provided, DC-nets are loosely analogous to proof-of-work or -stake protocols where bandwidth is the resource with which security is closely tied.

In general, no one solution is superior to all other solutions and different use-cases may require different levels of anonymity. In this post, we focus on network-anonymization of Ethereum's execution pipeline, where maximal sender anonymity at the network level is the primary goal. As a result, we accept that achieving this level of anonymity will likely require paying a cost in bandwidth and/or latency.

TEEs to the Rescue#

A recent anonymous communication protocol called ZipNet made a simple, but powerful observation. When designing an anonymous communication protocols, many of the computational and bandwidth inefficiencies stem from the need to ensure liveness, rather than anonymity. Leveraging this observation, ZipNet ensures liveness with the help of TEEs and ensures anonymity via classical cryptographic means. Should a TEE be broken, the system may become unresponsive, but anonymity does not rely on the security of TEEs.

In ZipNet clients send messages in synchronous rounds through an anytrust group of servers. ZipNet is highly efficient in terms of latency, has a moderate bandwidth overhead when compared to sending the messages not anonymously, while providing strong anonymity guarantees at the same time. Unfortunately ZipNet has one major weakness: it becomes unresponsive as soon as a single server is offline.

Flashnet#

We propose a new approach for anonymous broadcast that, like ZipNet, uses TEEs to ensure liveness, but relies on classical cryptographic means to ensure anonymity. In contrast to ZipNet, however, our system remains live even when some of the servers go offline. We provide the strongest level of anonymity in the sense that no broadcasted message can be attributed to a particular client, and achieve low latency, at the cost of moderate bandwidth overhead. From a security perspective, we consider an adversary that can monitor all network traffic and may even be in control of a constant fraction of the parties in the anonymous communication system.

At a high level, our system consists of three roles: clients, servers and a leader.

Clients are the ones who want to anonymously send messages. They may be malicious and try to disrupt the system. We assume that each client runs a TEE locally. If a client does not have a TEE, they may delegate to somebody who does have one, but this comes at a cost in terms of trust assumptions, since now they would need to rely on the TEE security for anonymity and not just liveness. This assumption can be relaxed to a non-collusion assumption on the clients, but would increase protocol complexity, so our first iteration assumes TEEs on the client side.

Servers form a group of machines among which we assume at least half to be honest. These machines receive encrypted traffic from the clients. The servers decrypt the incoming traffic, transform it into shares of the final output, and forward these shares to the leader.

The leader receives shares from each server and produces the final output, which it then gossips to a public mempool. Even if some of the servers are unresponsive or outright malicious, the leader can verifiably produce the correct output, as long as sufficiently many servers sent a message.

User-facing example of Flashnet flow.

In slightly more detail the high-level protocol works as follows:

- Each client locally prepares an empty array data structure and places their message in some random location in that array.

- Then, the client secret shares their array among the servers.

- Each server receives a share from each client and can locally add those shares together, resulting in a share of the sum of the individual vectors. Then each server can forward their share to the leader, who can use all shares to reconstruct the final output.

- The key observation here is that messages are stored in random places in the array that are detached from their identity, thereby ensuring anonymity. We note that client messages may collide in the same slot, but our protocol takes care of this by using a slightly more sophisticated data structure instead of a plain array.

Lightweight cryptographic checks keep servers honest and the client-side TEEs ensure that the clients prepare their arrays correctly and do the secret sharing honestly. Without the TEEs enforcing well formed inputs, a malicious client could incorrectly fill all the locations in their array with random values, leading to a summed vector that sums to garbage. This would break liveness, but not anonymity. In this short overview, different honest messages could accidentally end up in the same array cell. For brevity, we omit the technical details of how this is addressed to a future more technical blog post about our protocol.

To protect the addition step from a malicious server, each client authenticates their secret sharings with additively homomorphic vector commitments - i.e. each client sends a commitment to their array, allowing servers to compute a commitment to the sum of all client arrays without learning individual inputs. The binding properties of the commitment scheme ensure that no server can publish anything other than the honest share it should be publishing.

In our decentralized blockbuilding phases, Flashnet fits squarely into Phase 2, Distributed Building. At this stage, computation is distributed across specialized actors such as simulators, searchers, aggregators, but final block selection remains explicit and centralized. We expect BuilderNet's design to evolve to more effectively incorporate mechanisms like Flashnet and that Flashnet variants can eventually be incorporated directly into MCP-like designs like FOCIL, but we are pleased that deployment can be done today without major protocol changes.

Conclusion#

Flashnet is one example of how privacy, scaling, and decentralization converge at the blockbuilding layer. By treating block production as a distributed coordination problem rather than a monolithic builder or a protocol toggle, we can improve execution quality, reduce censorship risk, and preserve Ethereum's security model. BuilderNet and the broader path toward SUAVE are not abstractions. They are an in-production R&D sandbox where Ethereum can explore these tradeoffs under real adversarial and economic conditions, complementing L1 and L2 protocol work rather than competing with it. This post is one piece of a broader effort to make that coordination layer legible—and to invite the community to help shape it.