This article examines the application of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) in the Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) space. Our approach allows searchers to blindly backrun user transactions using FHE. This prototype demonstrates how a searcher can compute the future price of a UniswapV2 pool over a user transaction, keeping it encrypted throughout the process. Although this method is not currently practical for deployment, it serves as a foundation for future improvement and expansion, which we discuss in the conclusion.

Thanks to Sarah Allen and Leonardo Arias their feedback on the initial version. 🙏 This work was recently presented at ETHCC.

Introduction

In this article, we draw our attention to the specific facet of arbitrage within the MEV domain. Such arbitrage opportunities arise when the price of an asset on the blockchain differs from the price at which the same asset trades on other markets.

We present an approach that enables backrunning, a process where a transaction is crafted to be executed immediately after a target transaction to benefit from its impact on asset prices. Backrunning is at the heart of arbitrage and liquidation strategies and does not usually negatively affect retail users. However, the competition for backrunning opportunities in the public mempool has led to negative consequences, such as increased transaction fees. In this work, we leverage confidential transactions to technically guarantee that users who create the arbitrage opportunity do not pay with execution price for the backrunning opportunity they generate.

To mitigate this, we explore a solution that allows searchers to backrun encrypted user transactions while retaining the ability to program part of their strategy. This work builds upon a precedent study (https://writings.flashbots.net/backrunning-private-txs-MPC), showcasing the feasibility of extracting arbitrage-MEV through a sophisticated three-party protocol secured by a cryptographic protocol following the concept of secret sharing. While functional, this approach faced challenges, notably the high bandwidth requirements inherent to this type of cryptographic protocol, making it impractical to run across the Internet and the high computational overhead when opting for the most secure setting.

We want to reassess that, like the preceding study, this work is merely a feasibility test and does not imply any new direction for future Flashbots products. Our focus at this stage is to open the space for exploration rather than create a practical solution.

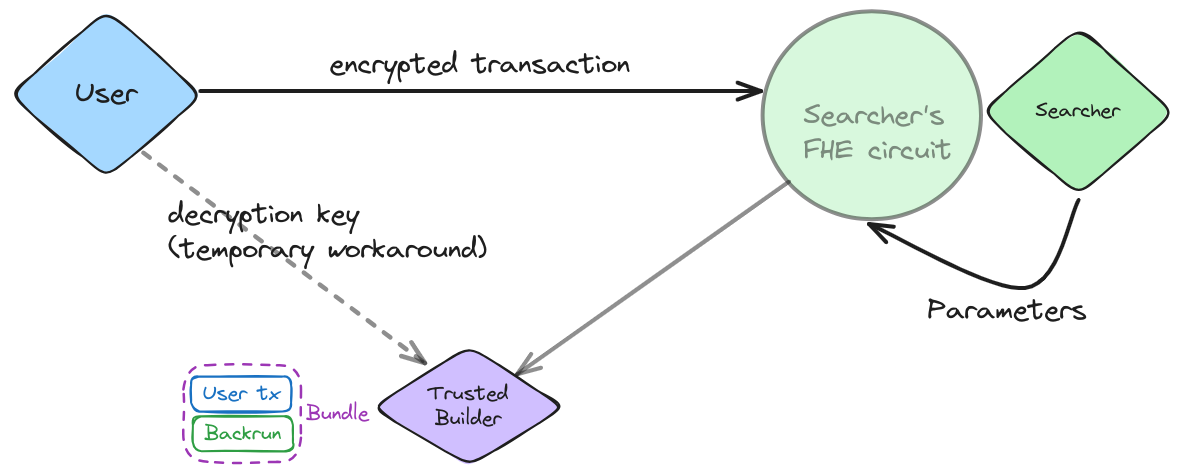

The original version of the protocol utilised techniques such as Shamir Secret Sharing to achieve confidentiality and security in the design process. Our alternative design is based on Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), where the user inputs a complete and encrypted transaction into a new FHE backrunning protocol. In concert, the searcher inputs a set of constraints and parameters to guide their strategy. This approach enables both parties to maintain confidentiality, with the encrypted output of the function being sent for decryption to a block builder.

To better illustrate this problem, we consider a simplified scenario involving a single user, searcher, and trusted builder. The user submits a transaction, and the searcher sends a backrun transaction to the builder, responsible for including both transactions in the same block without causing worse execution for the user.

Background

MEV and Suave#

If you're here, chances are you know pretty well what MEV is, but here's a recap. Block producers' ability to dertermine the transaction order in a block can lead to what is termed as Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). This phenomenon involves extracting value beyond the standard rewards and fees associated with transaction processing by controlling the sequence in which transactions are included in blocks. Certain kinds of MEV extraction can disrupt the smooth functioning of blockchain networks and introduces inefficiencies, raising concerns regarding fairness and security and hindering the progress of new applications built atop blockchain networks.

MEV is not limited to blockchains; it's present in other applications under different kinds of miscoordination problems. We have discussed this in the context of AI agents, but this is a story for another day.

A wide array of products mitigate MEV by offering the option for user transactions not to transit via the public Ethereum mempool, where they were historically spotted by searcher bots. Most rely on placing trust in a centralised mediator between all parties in the transaction supply chain to guarantee their integrity. Meanwhile, researchers explored avenues ranging from tweaking consensus mechanisms to crafting tools safeguarding users from MEV extraction, as detailed in this overview paper (https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.10878). One notable strategy deployed by Shutter (https://shutter.network/) involved encrypting transaction data until they were securely included in a committed block, effectively preventing sophisticated transaction ordering tactics reliant on real-time analysis by keeping the data fully blind to an external observer until the order in which they appear in the blockchain cannot change anymore.

Other researchers, including some from Flashbots have argued that preventing all forms of MEV extraction is 1) futile as it will reappear somewhere at the edges of your context, and 2) is not the most economically efficient thing to do for the overall environment. As such, plain encryption that hides every transaction field until committed to a block doesn't really cut it for our aim.

Programmable privacy can unlock the potential of MEV applications by giving app developers a new tool to better control the flow of information in an out of their protocols. Instead of removing a mechanism from the market, programmable privacy introduces safeguards keeping elaborate actors in check while allowing for efficient markets with empowered users end-users. We have charted a path towards the full realisation of this vision with the Suave roadmap. Our journey towards a full-fledged Suave involves taking a novel point of view on the security guarantees offered by Trusted Execution Environments like Intel SGX or TDX. This does not mean we shouldn't explore alternatives to confidential computing using TEEs, and it is also a way for us to better understand how Suave can serve a myriad of use cases that will not be TEE-native but would benefit from their properties.

Of course, today's state-of-the-art encrypted computing techs are far from confidential computing regarding performance, developer experience, and the breadth of use cases they can support. That said, we can still carve off portions of a bigger problem and attempt to solve smaller, well-bound problems using pure cryptography (and a few assumptions), as we will see in this article.

FHE for blockchain applications#

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is an advanced form of encryption that permits computations on data without revealing the data itself. By allowing operations on encrypted data, FHE ensures that sensitive information remains protected, even if the computational environment is not fully trusted. This property is significant for data confidentiality because it enables secure data processing and analysis while ensuring the underlying data remains confidential. In traditional encryption schemes, on the other hand, data must be decrypted before any computations can be performed, exposing it to potential threats. FHE's potential to revolutionise blockchain technology's security and privacy is fascinating, as it allows confidential off-chain computing and is well-suited for many applications that do not demand an extravagant amount of resources, just like smart contracts. In fact, FHE has been presented as a credible solution to implement privacy-preserving smart contracts in previous studies.

This vision has proved popular in the Ethereum ecosystem, with several projects now leveraging FHE as the underlying layer of their privacy-preserving smart contract platforms. Notable among them is Inco, which utilises FHE to enable secure computations on encrypted data, ensuring data privacy while performing complex tasks focusing on gaming mechanisms. Another significant project is fhenix, which operates on an EVM-compatible layer-2 network powered by an FHE-enhanced EVM. Fhenix uses FHE under the hood to provide a private programming environment for smart contract developers that falls in the realm of co-processors.

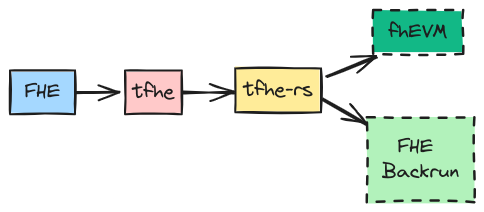

Inco and Fhenix rely on the same FHE scheme: TFHE (Torus Fully Homomorphic Encryption). The TFHE scheme is a particular implementation of FHE that excels in handling complex logic, comparisons, and arithmetic operations. TFHE has become popular option for blockchain applications since it was initially introduced by Zama in their fhEVM codebase. TFHE was designed to be particularly efficient for evaluating binary circuits. Still, it supports all types of short or big integers and thus covers all the data types that an Ethereum smart contract might manipulate. Its advantages include low latency for gate-by-gate computations and the ability to execute bootstrapping rapidly, which is crucial for maintaining the freshness of encrypted data and executing complex functions. Multiple implementations of TFHE are available and are becoming more and more performant with each release. In this work, we leverage Zama's tfhe-rs, the Rust library underpinning fhEVM.

This work builds on tfhe-rs, just like the increasingly popular fhEVM. tfhe-rs is a Rust library implementing the TFHE scheme.

Methodology

Settings and Security Assumptions#

In the scenario we are considering, there are three distinct parties involved:

- A user who wants to share their data but only if their privacy is guaranteed before any transaction takes place.

- A searcher who aims to blindly backrun the user's transaction using a predefined algorithmic strategy.

- A block builder who receives the ordered transactions.

This study focuses only on the user and the searcher, as the builder does not participate in the backrunning process. The builder's role consists of accepting the resulting bundle containing the user's and searcher's transactions and inserting them as they are into a candidate block. Both the user and the searcher trust the block builder, who has the authority to securely decrypt both transactions in the bundle and insert them into a block. A more realistic scenario would involve a public key setting and a private key shared among a group of validators via a Threshold-FHE protocol, but this is beyond the scope of this study.

This setting uses a secret key and the default cryptographic parameters provided by TFHE-rs, which ensure at least 128 bits of security according to the latest versions of the Lattice Estimator (https://github.com/malb/lattice-estimator). As a preliminary step to running this protocol, we assume the builder can securely generate and share its secret key with the user over a secure communication channel.

Protocol Design#

One key aspect of guaranteeing pre-trade privacy to the user sending an encrypted transaction is limiting what the searcher can do with it. Encryption is the first step towards achieving this design goal since the searcher does not get any feedback on the computation's outcome: the protocol produces either a profitable backrunning transaction or an empty one.

The FHE declination does not allow the searcher to program the full strategy. Instead, it follows a two-step logic that first decodes the underlying fields of the encrypted transaction using an FHE RLP (Recursive-Length Prefix - RLP is the format used to serialise Ethereum transactions) parser then calculates the optimal amount for the searcher to buy in the backrun.

The RLP parser pulls out the necessary fields to calculate the amount and verify against the searcher's acceptance criteria. Searchers usually focus on specific token pools, which are encoded as matching criteria in the strategy's parameters. In this first phase, the goal is to ensure that the input transaction data adheres to criteria that could affect the profitability of the arbitrage by potentially incurring high execution fees for the searcher, such as gas price or limit.

The logic involves systematically reading specific bytes from the input transaction data, comparing them with values from the searcher program, and making modifications as needed. Throughout the process, an encrypted "match" boolean tracks whether all the conditions are met. If any condition fails, the "match" is set to "false," indicating that the transaction doesn't meet the criteria specified in the searcher program. At the end of the backrunning logic, the FHE protocol generates an empty transaction filled with zeroes if any of the steps set the "match" boolean to "false." This approach caters to the inability to handle branching alternatives in FHE computations and allows for an early protocol abort.

The second central element of the protocol is the arithmetic calculation that allows the searcher to derive the amount of tokens to buy to generate a profit greater than what they have specified in input to the strategy.

Uniswap V2's pricing function#

The Uniswap v2 pricing function's simplicity enables us to calculate the maximum amount of tokens for a given input trade. An arbitrage opportunity emerges when the decentralised exchange rate deviates from centralised exchanges like Binance. In a two-leg, non-atomic arbitrage strategy, the searcher will buy assets on Uniswap before selling on Binance for a profit, thus rebalancing prices across the two exchanges and pocketing a profit. To do so, our searcher must calculate the amount of tokens to purchase on Uniswap based on the future price of the assets determined by the pending user transaction.

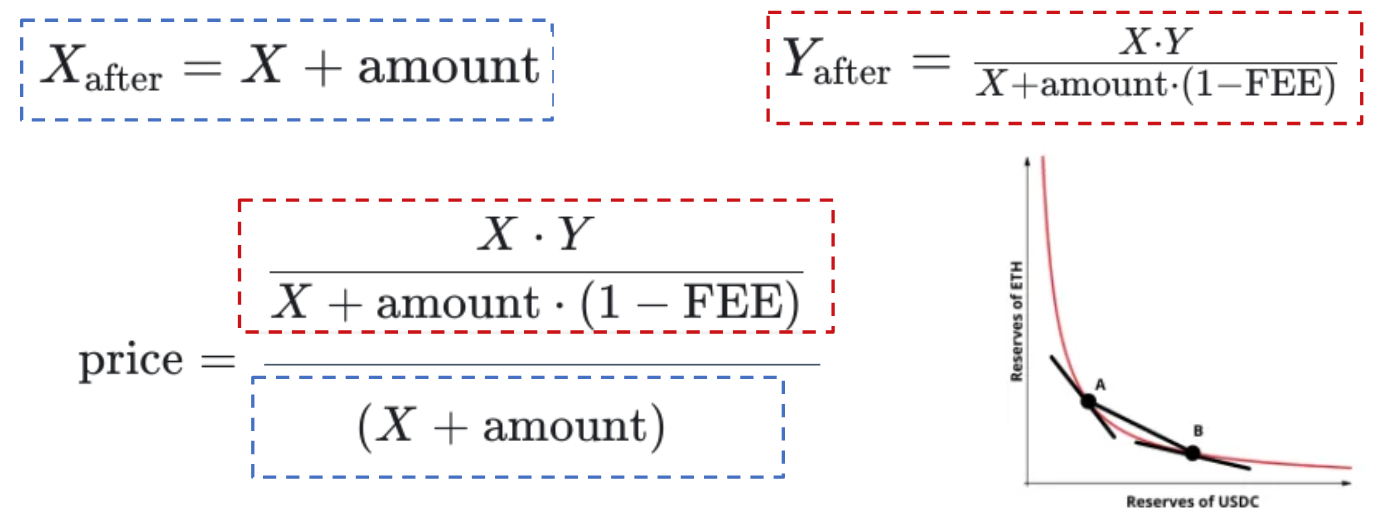

Uniswap v2 defines the price of an asset as the ratio of tokens in the pool, X and Y, such as USDT and WETH. Users incur a fixed fee of 0.3% when buying or selling assets, which impacts the price. The pricing function allows users to determine the number of tokens they can receive by selling a specific number of tokens up to a target price.

To execute a backrun on Uniswap v2, a searcher must consider the market price on the centralised exchange, the pricing function, and the state of the Uniswap v2 pool. By applying the pricing formula, searchers can calculate the amount of tokens they can buy up to a specific target price and compute their profit. This simulates the effect of the pending user transaction before it is even included on-chain to generate the optimal backrunning transaction that will be inserted right after it in the block.

The Uniswap V2 price equation can be fully solved provided one knows the current state of the reserves, and the amount of the pending swap. It is simply the ratio of the updated reserves, whose relationship is determined by the constant product formula represented on the plot at the bottom right.

Arithmetic calculation#

Now that we have an idea of how the Uniswap v2 pricing function works and how it can be computed outside of the smart contract let's examine the equation presented in https://writings.flashbots.net/backrunning-private-txs-MPC, reproduced here for clarity:

In this equation, X represents the reserve at the start of the swap of token A, and Y represents the reserves of token B. The searcher provides the constants FEE, PRICE, and PRECISION as part of the strategy's parameters, except for X and Y, which depend on the encrypted user transaction.

The primary obstacle in implementing an FHE version of this equation is the division by a scalar and, more significantly, the calculation of the square root of an encrypted number. We employ a simple strategy based on the Newton method to overcome this, limiting the precision to 5 rounds.

The division and square root operations are the slowest components in the FHE computation, with the latter requiring approximately 20 seconds on an AWS hpc7a.96xlarge server. This emphasises the need for more efficient techniques to optimise these operations.

Data types#

The UniswapV2 smart contract implementation represents the tokens' reserves as 112-bit unsigned integers. In the FHE version, we use a 128-bit unsigned integer supported by tfhe-rs. Handling such big integers is not simple in FHE, particularly when using the TFHE scheme, which, as we have seen earlier, has short integers and booleans as native data types.

To handle fractions, which are not supported by the EVM, Uniswap uses a workaround that involves representing fractions as 224-bit values, with 112 bits for the integer part and 112 bits for the fraction. As the calculation progresses, we adopt 256-bit unsigned integers to avoid any risk of overflow in the encrypted multiplications and subsequent operations.

Evaluation#

In this evaluation section, we delve into the performance metrics of our protocol, assessing its efficiency and scalability. We will detail the results exposed in the table below. Of particular interest is the examination of the bandwidth requirements of the protocol, considering the trade-offs between performance gains and hardware requirements as they represent the discrepancy between secret-sharing-based protocols and FHE. Hardware requirements, on the other hand, reflect the centralisation degree of the protocol, as stronger hardware requirements will limit the potential number of participants.

| Phase | Runtime 128-bit (seconds) | Memory (kB) | Runtime 80-bit (seconds) | Speed-up over 128-bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLP (Clear) | 36.706 () | 331,992 | 22.607 () | 1.62 |

| RLP (Encrypted) | 38.782 () | 334,000 | ||

| RLP (Clear + AVX512) | 31.787 () | 337,100 | 19.277 () | 1.90 |

| Amount | 1024.928 () | 432,116 | 619.325 () | 1.65 |

| Amount (AVX512) | 846.409 () | 462,146 | 504.351 () | 2.03 |

Performance Metrics#

Let's now examine the performance of our backrun protocol, evaluating different configurations for a single backrun. In the table above, we report the encrypted workload's performance, where the strategy's constants are represented using 128-bit cleartext unsigned integers. We compare the scenario where the workload runs on the searcher's machine with its homomorphic equivalent to assess the feasibility of executing the protocol on a third party's machine. These two settings represent two different scenarios, whether the compute-heavy part of the workload runs on the searcher's machine and thus the strategy parameters do not need to be encrypted, or whether we consider delegating the whole execution and then searchers also need to encrypt their parameters. The two scenarios are plausible. The first one assumes searchers are already equipped with server-grade machines. At the same time, the second is more favourable to decentralisation and opening the competition for MEV to small searchers without the necessary infrastructure.

We note that key generation and encryption steps are not reported separately, as their runtime is negligible compared to the core workload. These steps could be part of a preprocessing phase where users and searchers encrypt once, with the time cost amortised over multiple executions.

Our experiments were conducted on a 128-core Intel Xeon Platinum 8375C CPU running at 2.90GHz with AVX512 instructions enabled. The results reveal that the amount calculation phase significantly dominates the RLP extraction phase by two orders of magnitude. This is due to the series of homomorphic divisions required to approximate the square root using Newton's method, as specified in the searcher's optimal amount calculation Equation.

Impact of SIMD Optimisation#

We now focus on the impact of SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) instruction sets on FHE algorithm execution speed. Our analysis focuses on the TFHE scheme, which relies heavily on a fast bootstrapping operation that can be significantly accelerated using Fast Fourier Transforms (FFTs).

We compared AVX2 and AVX512 instruction sets and found that AVX512 offers a 20% speed increase over AVX2. However, AVX512 is not widely available in regular consumer-grade CPUs and usually requires high-end server hardware. This raises important questions about the trade-offs between performance gains and hardware requirements. While searchers can operate large server farms and even deploy GPUs or other hardware accelerators, these come with additional costs and infrastructure considerations. This analysis suggests strong hardware specifications might be required to rapidly roll out an FHE-based MEV-searching solution, thus limiting the number of teams participating in the protocol.

Key and Ciphertext Sizes#

Finally, let's analyse the impact of ciphertext expansion on data transfer demands in Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) schemes, particularly the TFHE version. FHE expands the size of encrypted data, leading to larger data transfers than the cleartext equivalent. However, when dealing with Ethereum transactions, the data size is relatively small, so the extra transfer demands are mainly due to the encrypted data.

In contrast, traditional MPC protocols require large data exchange, even with weaker security. Comparing our TFHE version to the original MPC backrunning protocol, we find the former more efficient regarding data transfer demands. The TFHE version has a server key size of 105MB and ciphertexts for transactions and strategies of 47MB and 20MB, respectively. Despite these larger ciphertexts, FHE is more efficient than secret-sharing-based MPC protocols.

Results and Discussion#

The feasibility of fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) for MEV extraction hinges on addressing significant computational challenges.

The stark difference in runtime and memory utilisation between the RLP parsing and amount calculation phases highlights the areas needing optimisation to make the protocol viable for real-world applications.

First, faster arithmetic over large integers will be required to unlock MEV-related applications at scale and provide searchers with a similar experience to what they are used to when designing their strategies. Our experiments highlighted two bottlenecks in the arithmetic phase of our backrunning application: the final division and the evaluation of a square root. In the current implementation, they boil down to the same primitive since we approximate square root using successive divisions as part of the Newton method. As such, the main target for applied cryptographers working on FHE schemes should be to accelerate big integer division.

Additional considerations must be addressed beyond the current protocol for practical deployment in blockchain environments. One major challenge is Ethereum's requirement for ECDSA-signed transactions. This necessitates that searchers inject their private keys as part of the encrypted inputs, demanding ECDSA signature operations within the encrypted realm. This requirement poses significant difficulties due to the modular inverses involved in ECDSA's signing algorithm, and the current state of the prototype skips this step as a result.

In summary, while FHE shows promise for confidential MEV extraction, the current implementation faces substantial overheads and limitations. Enhancing the speed of large integer arithmetic, particularly division, is critical. Moreover, integrating ECDSA signature capabilities within the encrypted domain is a complex but necessary step for real-world deployment. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for making FHE a viable solution for MEV extraction at scale.

Conclusion#

In this work, we have explored the application of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) to the problem of Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) in blockchain transactions. We have focused on the specific case of arbitrage, where a transaction swapping two tokens on a given market can create a price discrepancy in another market. Our approach builds upon previous work by Flashbots, adapting a secret-sharing-based protocol to an FHE one to reduce the overhead in data transmission.

We have presented a protocol that allows traders to blindly backrun a user transaction, executing certain conditions and arithmetic operations on the content of the transaction using FHE to mimic what is known as a searcher's strategy. This protocol uses the tfhe-rs Rust library and targets the UniswapV2 Decentralised Exchange (DEX).

Our evaluation has shown that while the protocol is feasible, it faces significant runtime constraints. We have identified several areas for future research, including handling multiple input transactions, overcoming ECDSA signature challenges, and extending the protocol to other forms of MEV and other DEXs.

While many challenges remain, our work provides a solid foundation for future research at the interface of MEV and encrypted computing. Our findings will stimulate further collaboration within the FHE community to address the open challenges and bring privacy-preserving protocols for MEV mitigation closer to real-world deployment.

We'll keep iterating on this prototype and new ones to identify more use cases where FHE could play a role in future blockchain applications. Increased FHE adoption likely happens via a better mutual understanding between FHE practitioners and MEV developers. We will need to cut some corners and refine assumptions to reach satisfying performances, and this can only happen at the interface of these two communities.

We're hiring#

If you'd like to join us on this journey to explore the benefits of programmable privacy for MEV use cases, you can apply here: https://jobs.ashbyhq.com/flashbots.net/be206742-9cac-4ad8-990e-623ef06123d3